Layers of History

Revealing the Bodenwieser dance legacy

Tangible items of performance such as costumes come with their own set of preservation needs and depending on their age and condition can sometimes be quite fragile.

In 2000, the Australian Performing Arts Collection received a donation of over 200 items relating to the career of dancer, choreographer and teacher Gertrud Bodenwieser. Made up of costumes, props, photographs and programmes, the collection documents the history of the Bodenwieser Ballet, a company she established in Sydney after migrating to Australia in 1939.

This story focuses on the most fragile costume in the Bodenwieser collection and the only one that pre-dates her time in Australia. Curator Margot Anderson looks back at the history of the costume and the influential woman who wore it. Conservator Bronwyn Cosgrove captures the process behind the costume's stabilisation and how her treatment has secured its preservation for a whole new audience.

Costume worn by Gertrud Bodenwieser in an unidentified solo performance, Vienna, c.1920. Gift of Barbara Cuckson, 2000.

Costume worn by Gertrud Bodenwieser in an unidentified solo performance, Vienna, c.1920. Gift of Barbara Cuckson, 2000.

Gertrud Bodenwieser

Born in Vienna in 1890, Bodenwieser began studying ballet under Carl Godlewski in 1905. The city was in the midst of a cultural boom at the time, playing host to modern dance pioneers such as Isadora Duncan, Ruth St. Denis and Loie Fuller.

By 1910, Bodenwieser had become disillusioned with the artistic conventions of classical ballet. Drawn to the freedom of modernity, she began to create her own style of movement, aiming to explore 'the most primordial powers of human sensibilities' through dance.

Bodenwieser made her public debut in 1919 at the Wiener Konzerthaus and was critically acclaimed for her unique style. Inspired by leading exponents of modern dance including François Delsarte, Émile Jacques-Dalcroze and Rudolf von Laban, she soon established her own school. Bodenwieser developed a dance method emphasising freedom of expression and physical well-being.

“Dancing is by no means merely a vehicle of artistic expression, or as a display in its exceptional flair for showmanship. It is also valuable as a well-nigh unrivalled method of implanting physical health and mental vigour.”

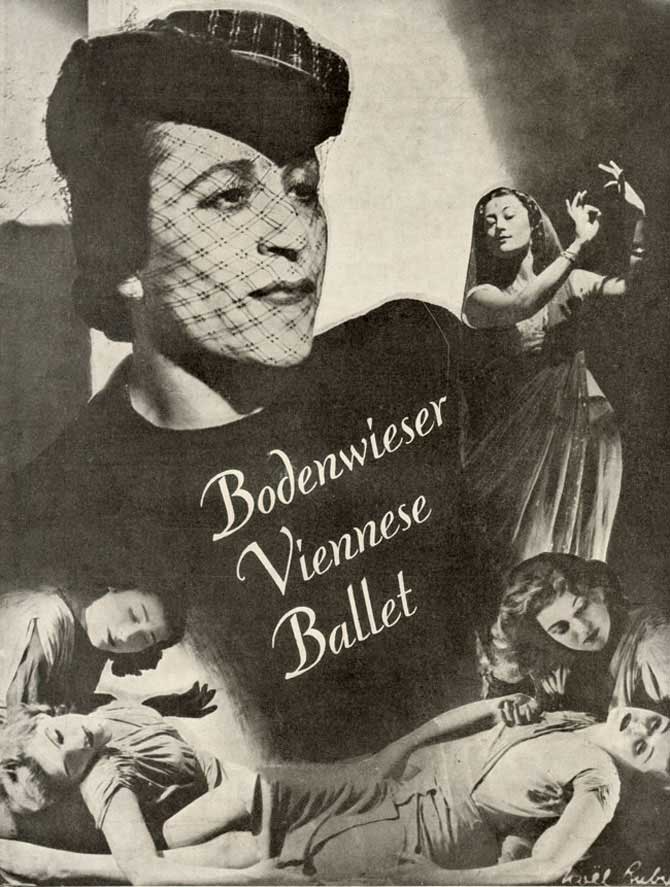

Bodenwieser Viennese Ballet programme cover c.1940.

Bodenwieser Viennese Ballet programme cover c.1940.

In 1923 Bodenwieser established the 'Bodenwieser-Gruppe' attracting a strong following with Viennese audiences. The ensemble launched their first tour in 1926, performing extensively throughout Europe. In order to meet audience demand, a second group was formed allowing simultaneous performances in different countries.

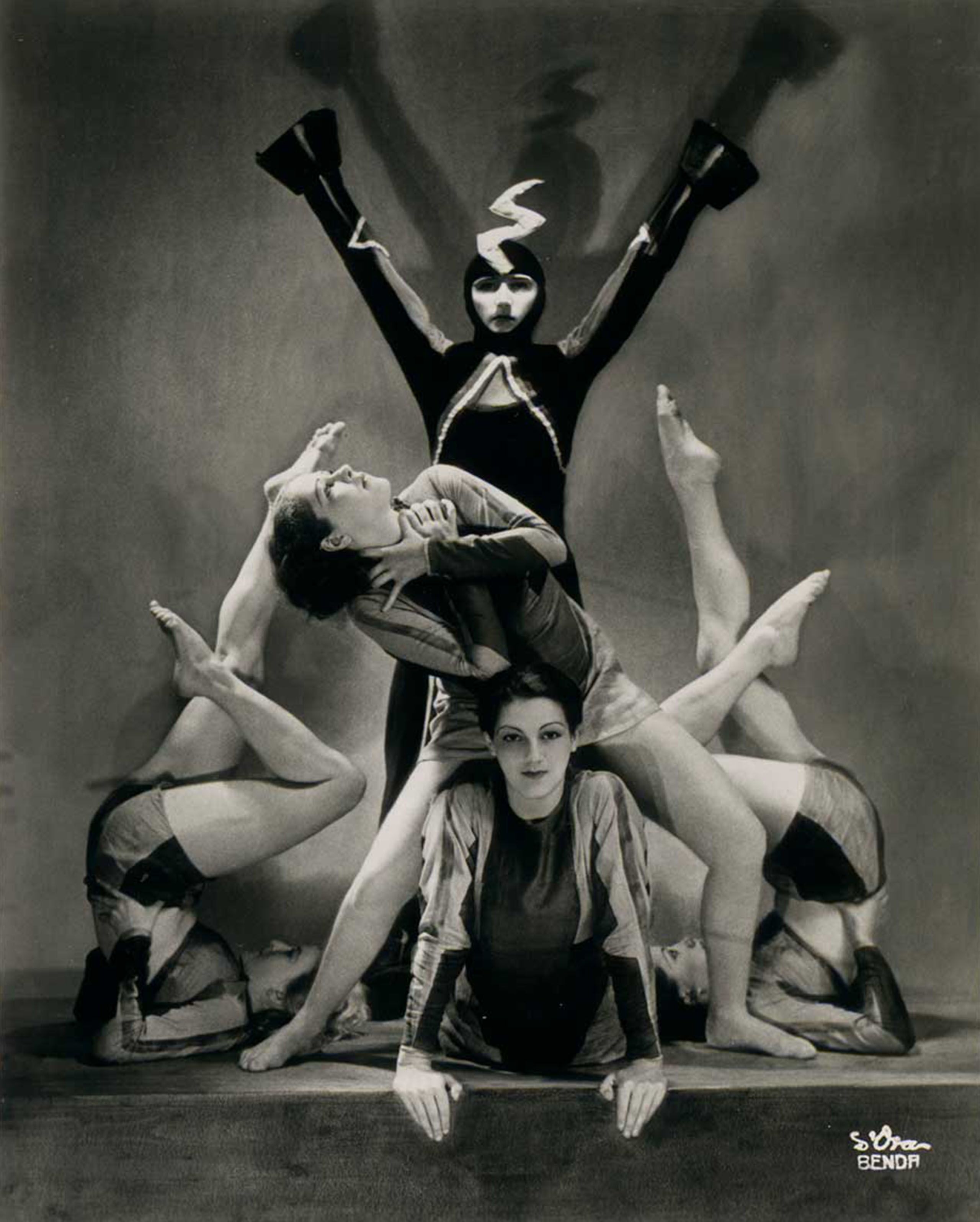

Bodenwieser choreographed close to 300 dance works during her career. Narrative-based dance dramas such as The Masks of Lucifer (1936) were balanced with more ethereal abstract works like Water Lillies (c.1937). A variation on the Viennese waltz Blue Danube (1940) was a particular favourite with audiences. Perhaps the most significant of Bodenwieser’s works was Demon Machine (1924), a masterfully devised response to the mechanisation of society with dancers moving as a group to depict a working machine.

In 1938, Bodenwieser and her husband, theatre director Friedrich Rosenthal, were forced to flee Austria when Nazi Germany occupied the country in the lead up to the Second World War.

Bodenwieser joined a group of her dancers as they toured South America and would never see her husband again. Many years later she learnt that he had died in Auschwitz concentration camp in 1942. She migrated to Australia in 1939 and opened a studio in Sydney where she began preparing an Australian tour for what would become the Bodenwieser Ballet.

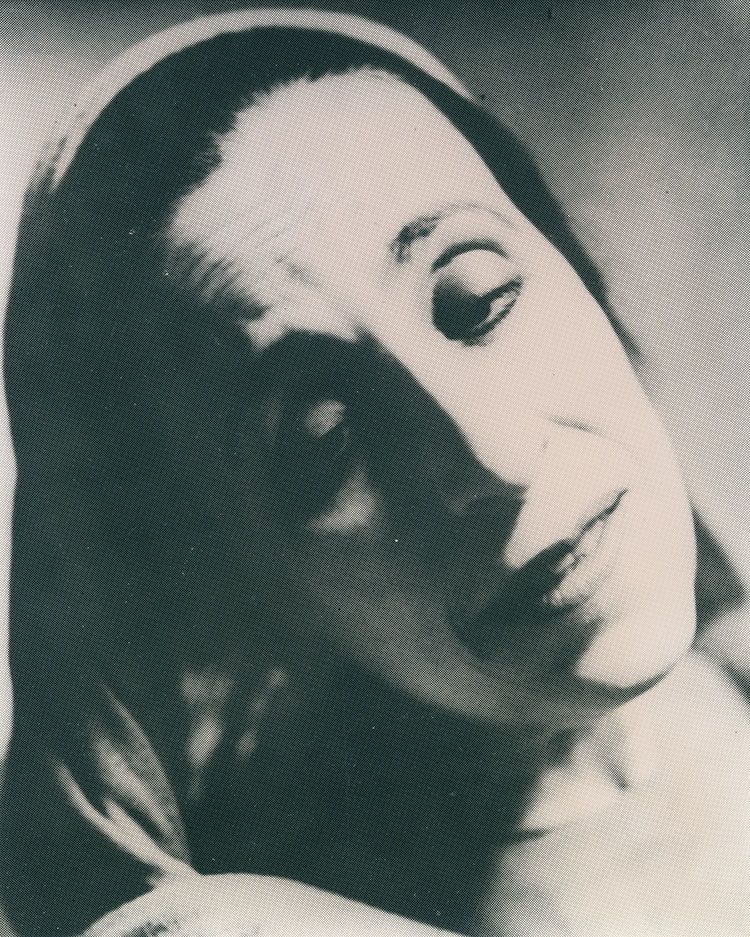

Gertrud Bodenwieser in O World, 1945. Gift of Barbara Cuckson, 2000.

Gertrud Bodenwieser in O World, 1945. Gift of Barbara Cuckson, 2000.

Evelyn Ippen and ensemble members in The Masks of Lucifer, Tanzgruppe Bodenwieser, 1936. Gift of Barbara Cuckson, 2000.

Evelyn Ippen and ensemble members in The Masks of Lucifer, Tanzgruppe Bodenwieser, 1936. Gift of Barbara Cuckson, 2000.

Eileen Kramer and Jean Raymond in The Water Lilies, Bodenwieser Ballet, 1951. Gift of Barbara Cuckson, 2000.

Eileen Kramer and Jean Raymond in The Water Lilies, Bodenwieser Ballet, 1951. Gift of Barbara Cuckson, 2000.

(From left) Moira Claux, Elaine Vallance, Nina Bascolo and Biruta Apens in the Blue Danube Waltz, 1953. National Library of Australia.

(From left) Moira Claux, Elaine Vallance, Nina Bascolo and Biruta Apens in the Blue Danube Waltz, 1953. National Library of Australia.

Ensemble members in Demon Machine, Tanzgruppe Bodenwieser, 1936. Photograph by D’Ora-Benda. National Library of Australia.

Ensemble members in Demon Machine, Tanzgruppe Bodenwieser, 1936. Photograph by D’Ora-Benda. National Library of Australia.

The Story Behind the Costume

“She brought one trunk from Vienna which held costumes for the South American tour and some personal items including this costume.”

This petite, hand-painted, golden ensemble was worn by Bodenwieser herself and is one of over 20 costumes donated by dancer and historian Barbara Cuckson in 2000. Together, the costumes help tell the story of the Bodenwieser Ballet and the impact the company had on the development of contemporary dance in Australia.

The Bodenwieser collection features costumes from works that were performed in Australia such as The One and The Many, Slavonic Dances and The Pilgrimage of Truth. Often designed and made by the dancers themselves, many of the costumes were constructed using heavy woollen fabrics and any embellishments were hand stitched or appliquéd.

Costume for Slavonic Dances, Bodenwieser Ballet, 1939. Designed by Evelyn Ippen. Gift of Barbara Cuckson, 2000.

Costume for Slavonic Dances, Bodenwieser Ballet, 1939. Designed by Evelyn Ippen. Gift of Barbara Cuckson, 2000.

In contrast, the costume worn by Bodenwieser features finely detailed paintwork trim, reflective sculpted elements and a tailored fit. It can only have been a delight to watch in motion. Details of the costume's history are currently unknown, however available information places it firmly at the beginning of Bodenwieser's career amidst the artistic circles of interwar Vienna.

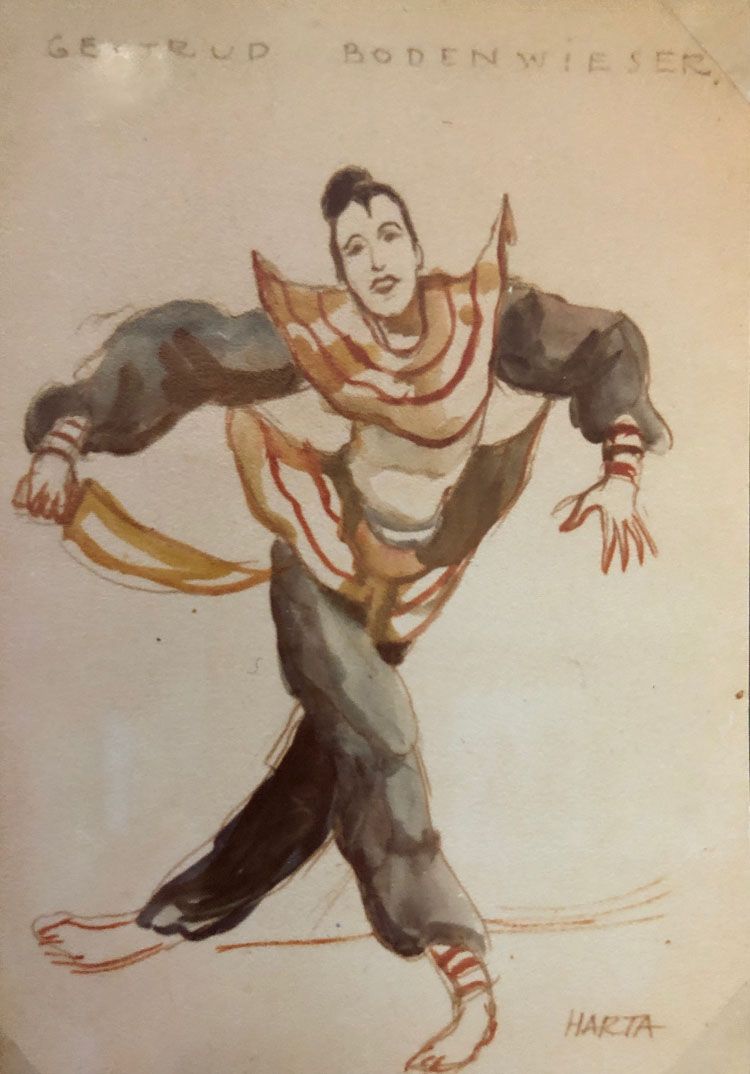

While the search continues for a photograph of Bodenwieser wearing the costume, it is thought to be depicted as part of a series of painted studies titled Tanzerinnen (Dancers) created by Hungarian artist Felix Albrecht Harta.

He was one of many innovative young artists based in Vienna when Bodenwieser performed her first solo recital. Harta's large circle of friends included artists such as Alfred Kubin, Wolfgang Born and Gustav Klimt, as well as notable writers and theatre makers of the day.

Bodenwieser's desire to challenge the traditions of classical dance and her expressive style of performance made her an appealing subject for both Harta and Born. While the artwork does not include the name of the production, the costume's distinctive silhouette and golden tones evoke a similar spirit.

The fragile condition of the costume has previously prevented it from being dressed on a form for display or photography. In order to showcase this unique item within APAC's new storage, research and education facility, it has recently undergone conservation treatment in Arts Centre Melbourne's first conservation lab.

In the following sections, conservator Bronwyn Cosgrove shares insights into this detailed and complex work.

Costume worn by Gertrud Bodenwieser in an unidentified solo performance, Vienna, c.1920. Gift of Barbara Cuckson, 2000. Gift of Barbara Cuckson, 2000.

Costume worn by Gertrud Bodenwieser in an unidentified solo performance, Vienna, c.1920. Gift of Barbara Cuckson, 2000. Gift of Barbara Cuckson, 2000.

Watercolour by Felix Albrecht Harta of Gertrud Bodenwieser, Vienna, c.1920. Image supplied.

Watercolour by Felix Albrecht Harta of Gertrud Bodenwieser, Vienna, c.1920. Image supplied.

Conservation

Conservation work started with the gold peaked collar, the most fragile component of the costume.

It presented considerable challenges.

Due to the cracked and delaminating (peeling) layers it had rarely been handled since acquisition.

In order to develop an appropriate conservation treatment plan, it was important to understand the materials present and how they were layered.

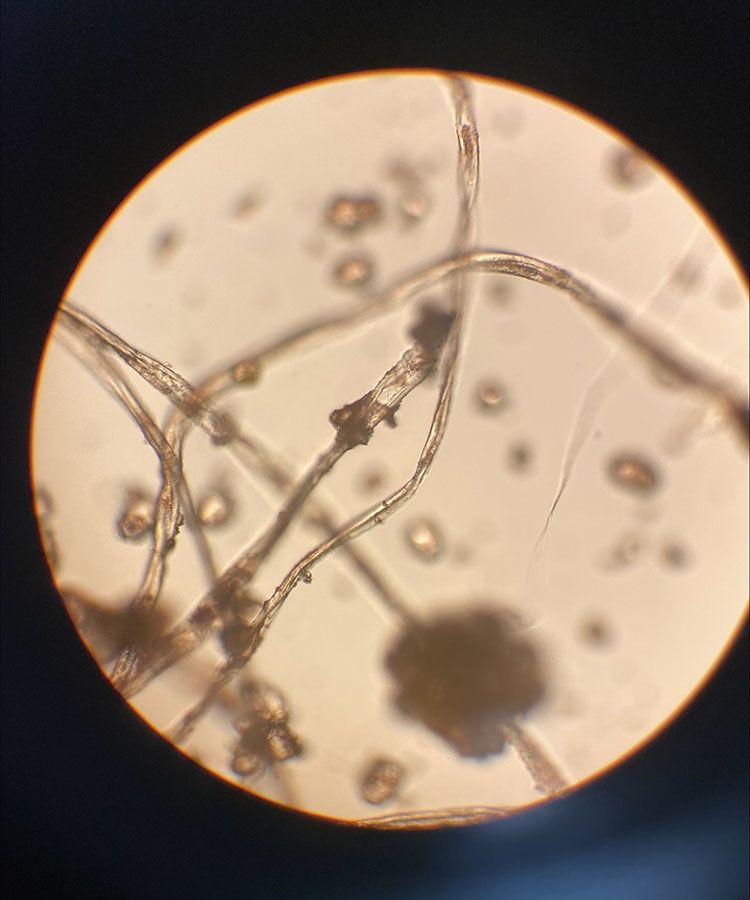

Using a digital hand-held microscope, the buildup of layers on the surface of the collar was revealed:

metallic paint...

...metallic foil...

and a composite of fibres in a beige base layer.

Using higher magnification, the fibres in the beige substrate were identified as cotton.

Scientific analytical techniques were used to identify the composition of the clumps visible in the microscope image, and the metallic foil and paint layers. These found that the beige substrate was a combination of starch and calcium carbonate, and the metal foil and metallic paint both contained copper and zinc.

Once the sensitivity of the materials to solvents and temperatures was understood, a suitable stabilisation method to secure the flaking layers was developed using a conservation grade adhesive and heated spatula.

In consultation with curators, a decision was made to focus the treatment on stabilisation, rather than restoring areas of loss. This approach honours the use and history of the costume.

The body of the costume is constructed from an orange twill weave fabric and lined with undyed cotton.

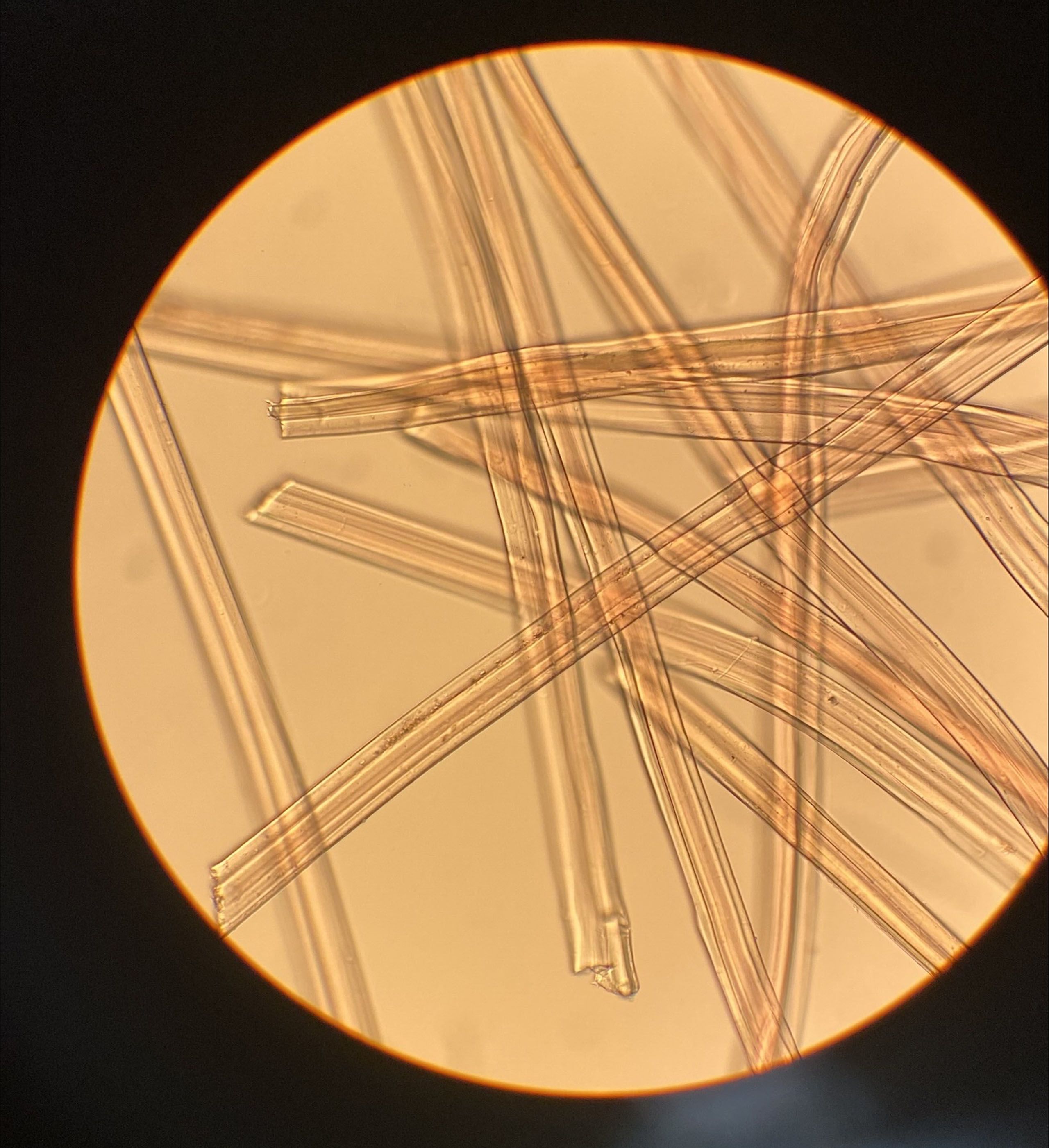

Under a microscope, the fibres have features matching regenerated cellulose. This class of fibres, derived from wood pulp, entered the fabric market in the 1920s as an alternative to silk and was rapidly adopted by the garment industry.

Using a single fibre sample, the fabric of the costume was identified as rayon.

The rear hem of the bodice is finished with a metal thread lamé peplum.

Under magnification, the twill weave is clearly visible.

The metallic weft yarns are metal foil wrapped around a fibrous core, interwoven with cotton warp yarns.

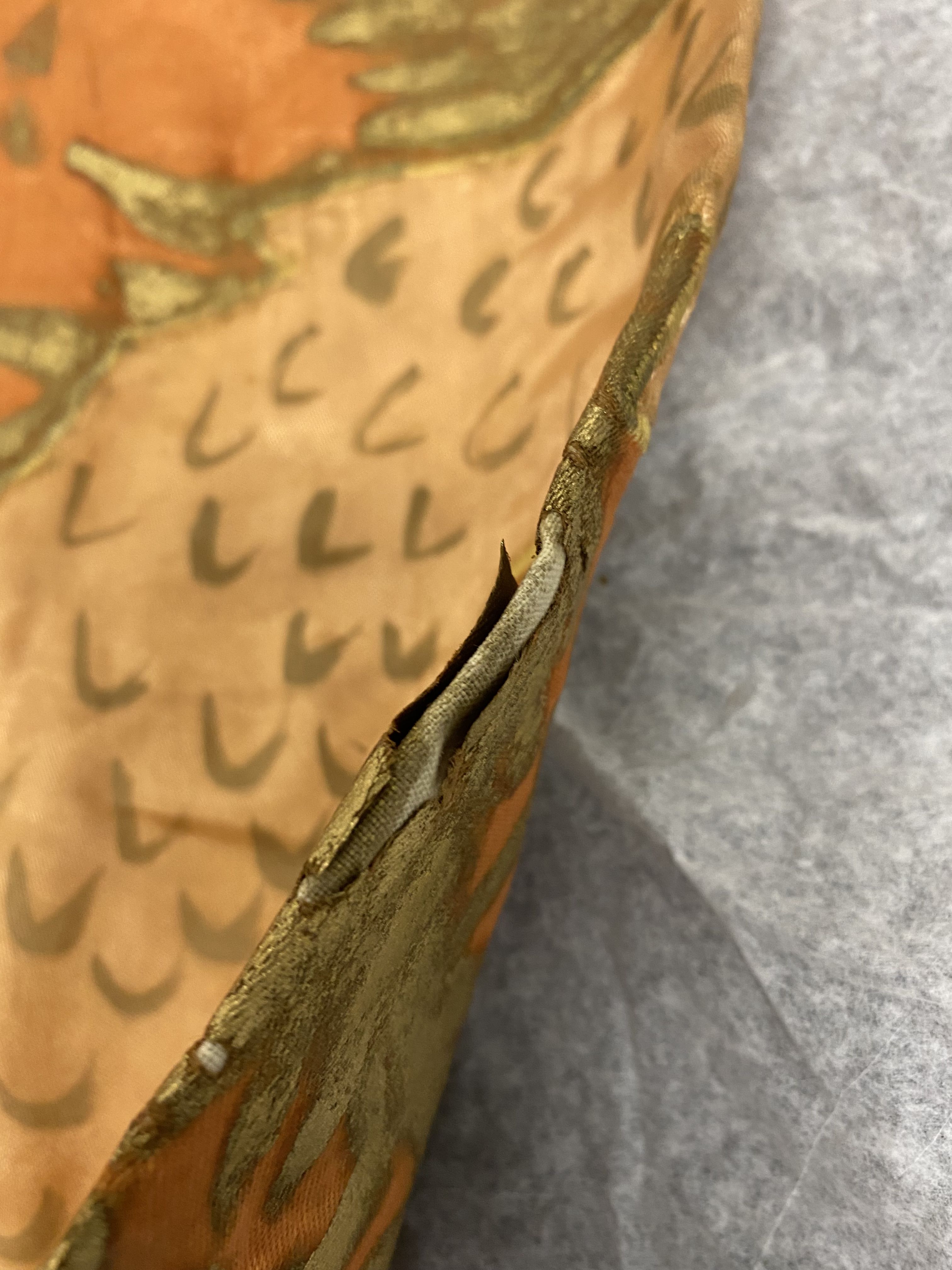

The trousers of the costume are decorated with dragons in appliqué fabric and metallic gold paint.

Over time, the metallic paint has hardened, causing the underlying fabric to crack.

This was particularly noticeable along the outer fold of the trouser legs.

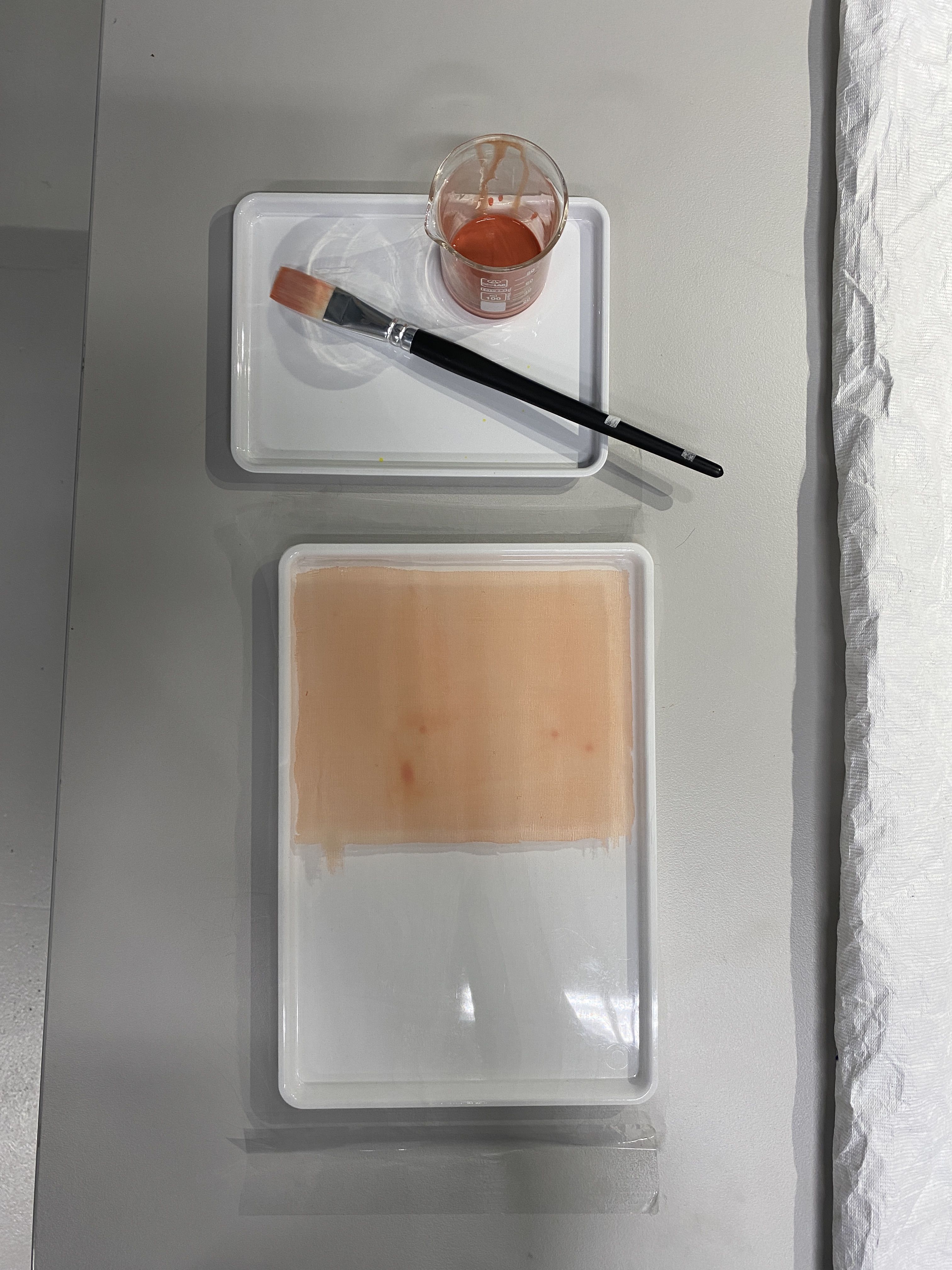

To treat this damage, toned silk crepeline, a lightweight sheer gauze, was coated with a conservation grade adhesive, that when dry, was applied behind these areas as a secondary support and activated using a heated spatula.

Before conservation, the sleeve cuffs were creased and the metal thread trim was frayed and loose in areas.

The creasing in the cuffs was reduced using carefully controlled heat and pressure, and the metal threads of the trim were aligned and secured with hand stitching.

Dressing

With treatment complete, the costume was ready to be mounted on a mannequin for display.

This process can be extremely time consuming as it requires sensitivity to the original wearer’s physique and the condition of the costume. It begins with sourcing an appropriately sized form, and hand stitching layers of padding in place to slowly build the correct body shape.

When it is time to dress the costume onto the mannequin, two people are required to ensure that the costume is carefully handled during the process. To support the 'fins' for display, pieces of lightweight card were cut and folded. These are held in position using small magnets.

The fragile nature of Bodenwieser's costume had significantly restricted the way it has been viewed and handled since it joined the Australian Performing Arts Collection. Thanks to conservation treatment and the dressing process we can now fully appreciate the form and lustre it has today. With further research into collections both nationally and overseas we hope to discover more about the costume in performance, what it meant to Gertrud Bodenwieser and why she brought it with her to Australia.

Credits

All photographs and objects are from the Australian Performing Arts Collection, Arts Centre Melbourne unless stated otherwise.

Special thanks to the following individuals and organisations for their contribution to this story:

Barbara Cuckson

Andrea Amort

Larry Heller

Eileen Kramer

Shane Carroll

Theatermuseum, Vienna

The Australian Ballet

Costume photography by Narelle Wilson

Materials analysis by Rosemary Goodall, Museums Victoria