Strange and Alluring

Extraordinary opera designs and costumes from a radical production

When the curtain came down on The Australian Opera's opening night performance of Nabucco on 12 August 1995, the creative team behind the production came out to take their bow.

As director Barrie Kosky, designer Peter Corrigan and lighting designer Nigel Levings took the stage, loud boos could be heard coming from sections of the audience. The boos were prompted by the production's radical direction and design. And for Kosky, at least, they were proof that he had achieved what he set out to do: to shake Australian audiences out of their complacency.

In the nearly thirty years since that first performance, the Australian Performing Arts Collection has acquired costumes from this production, as well as Peter Corrigan’s performing arts design archive.

Costume worn by Jonathan Summers as the title character in the Melbourne season of Nabucco, 1996

Curator Ian Jackson looks back at the controversy around Nabucco, and what it tells us about how art, ideas and audiences can make sparks fly on and off stage.

Costume worn by Jonathan Summers as the title character in the Melbourne season of Nabucco, 1996

Costume worn by Jonathan Summers as the title character in the Melbourne season of Nabucco, 1996

“Embrace the kaleidoscope of Nabucco and let yourself be whirled through the deserts of time, place and memory”

The Design Vision

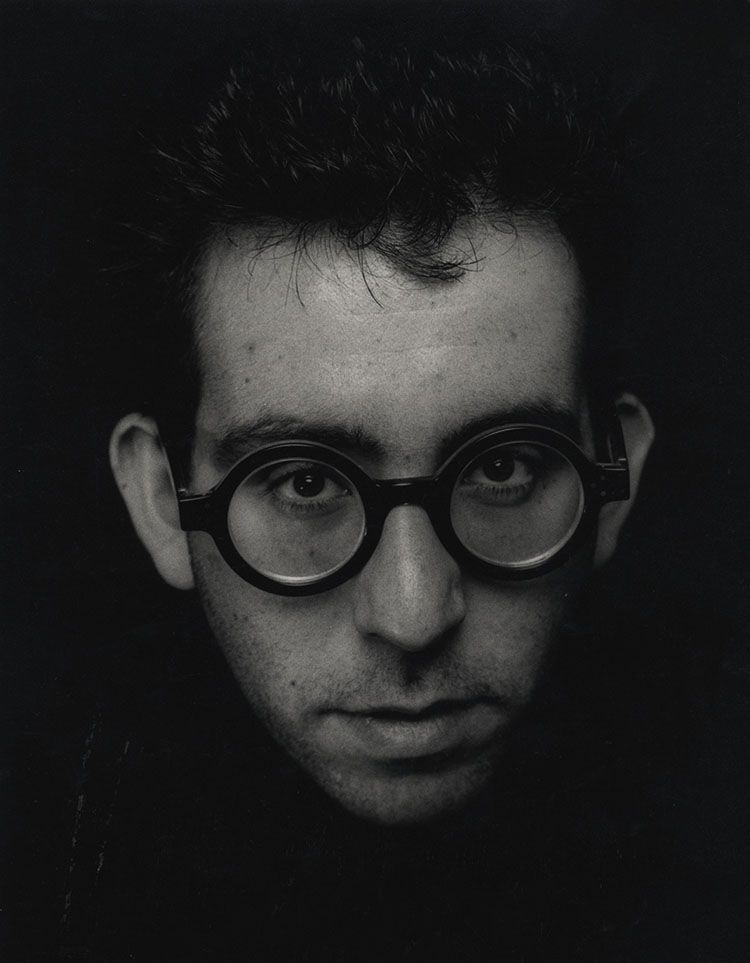

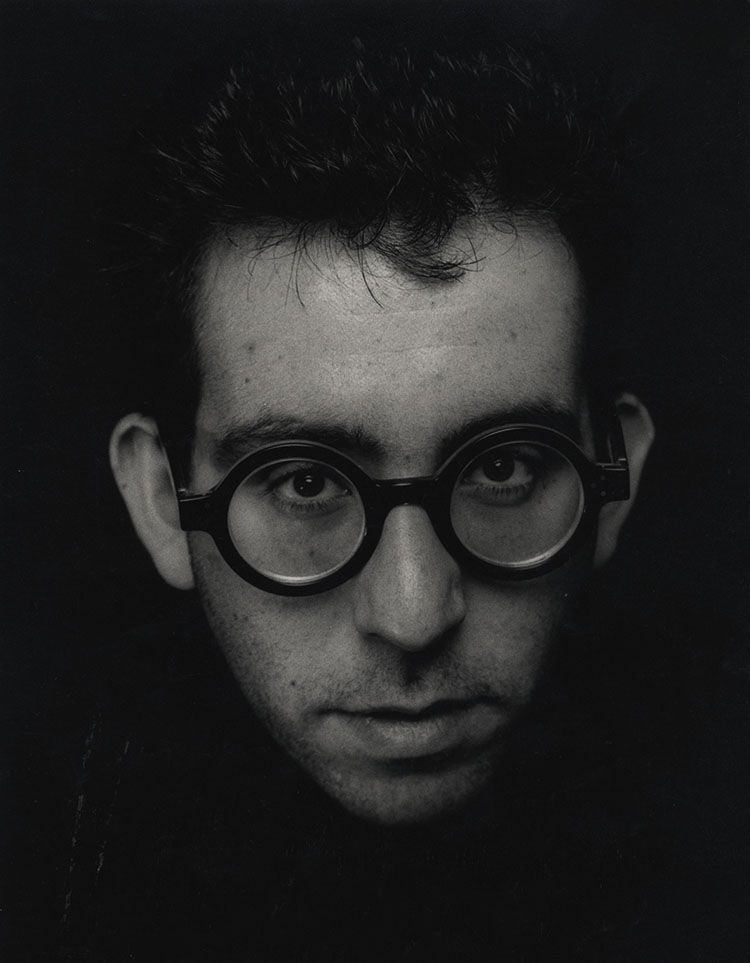

Barrie Kosky, then a 28-year old wunderkind of theatre, and Peter Corrigan, an established architect with a long interest in design for the stage, made for an unusual but effective partnership. As Kosky told the Good Weekend magazine just before opening night, “We have incredible rapport, yet we’re so different – the loud, funky, hysterical Jew and the quiet, rather ambiguous, but fiery Irishman”.

Barrie Kosky

Barrie Kosky

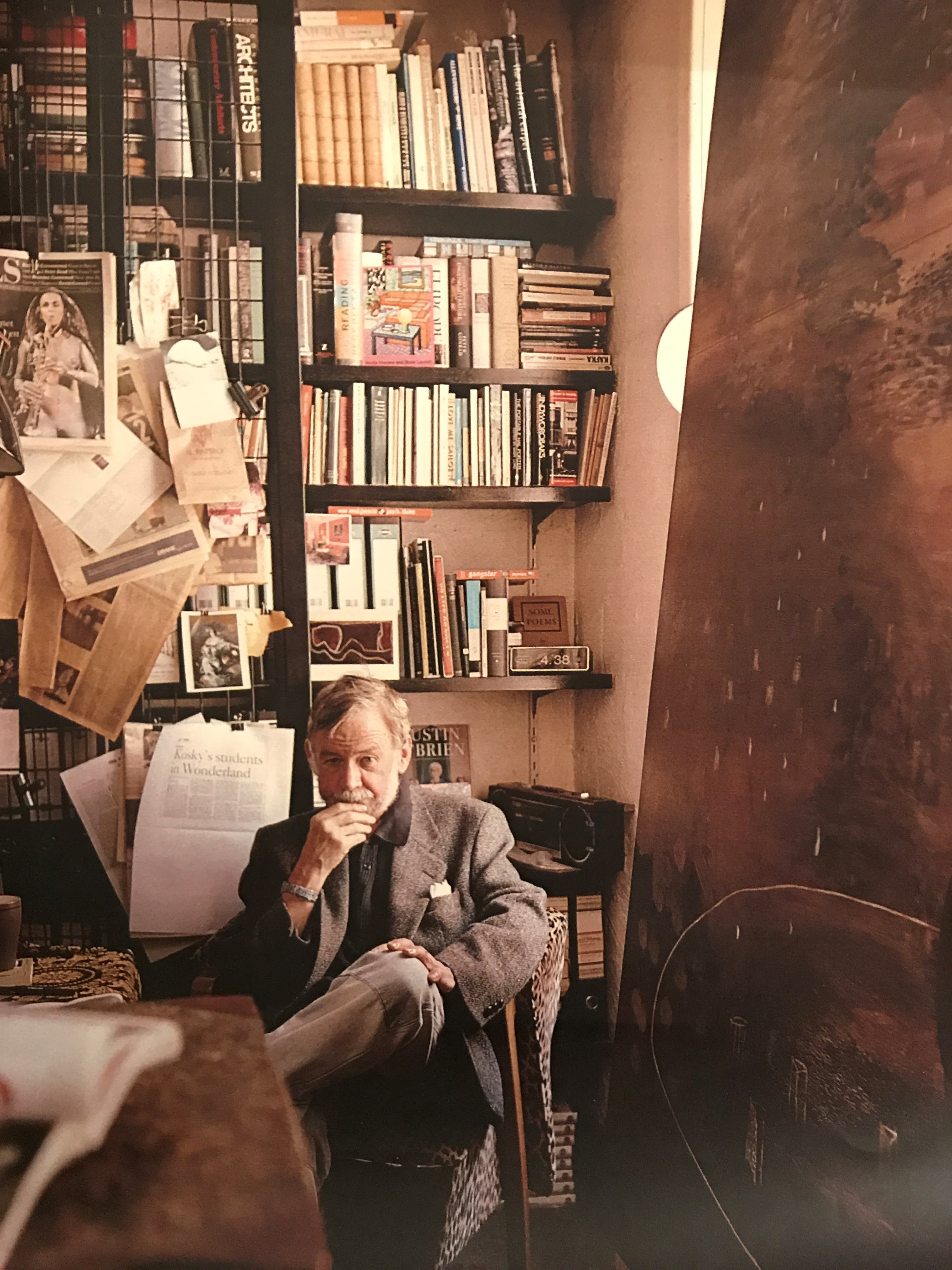

Both shared a view that for performing arts design, ideas matter more than beauty or period accuracy: Corrigan noted approvingly that “Barrie doesn’t want décor… but design that carries ideas, carries the debate forward”.

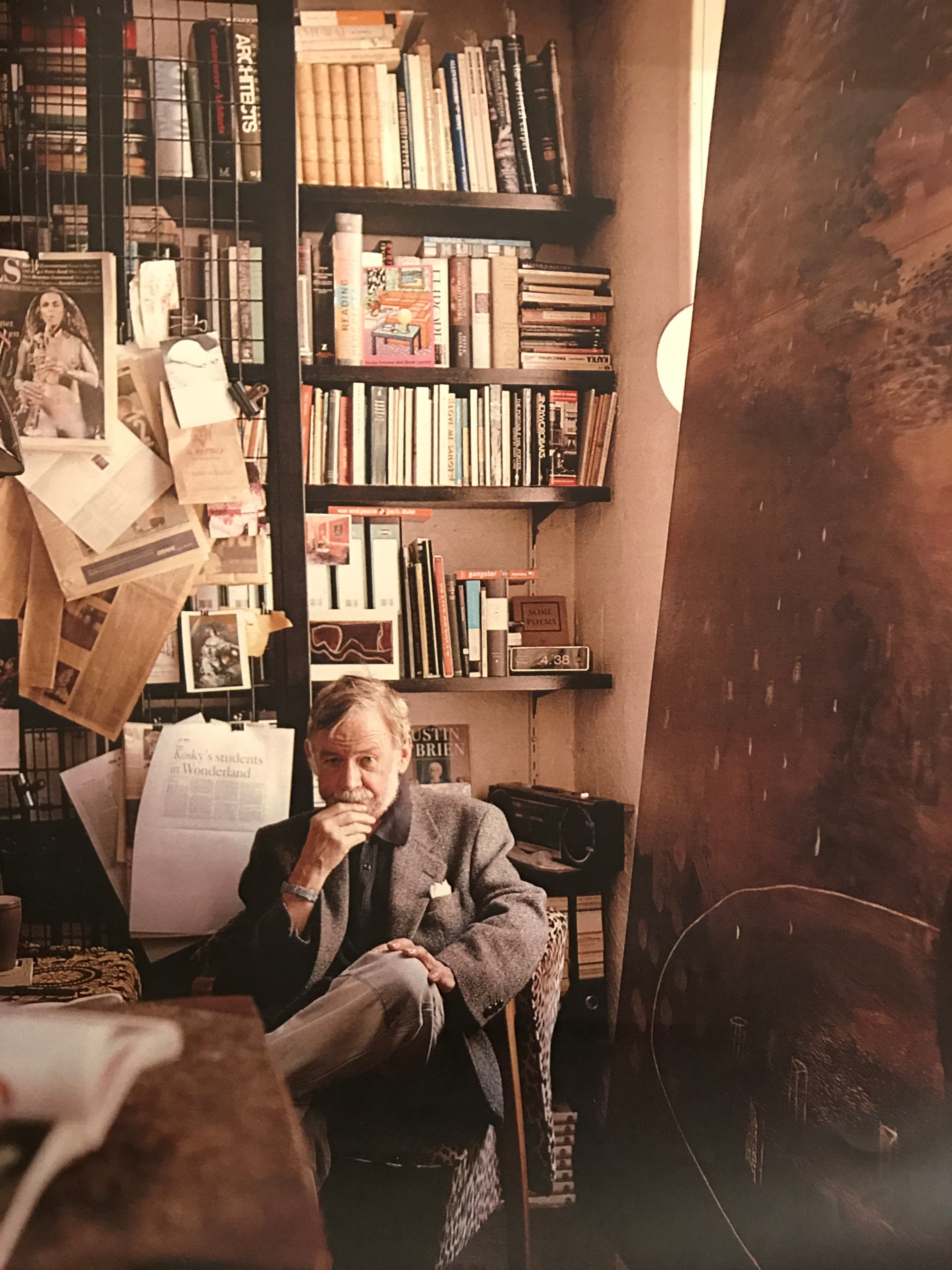

Peter Corrigan

Peter Corrigan

Kosky and Corrigan had been commissioned by The Australian Opera’s Artistic Director, Moffat Oxenbould, to replace their much-loved but ageing 1971 production of Giuseppe Verdi’s opera.

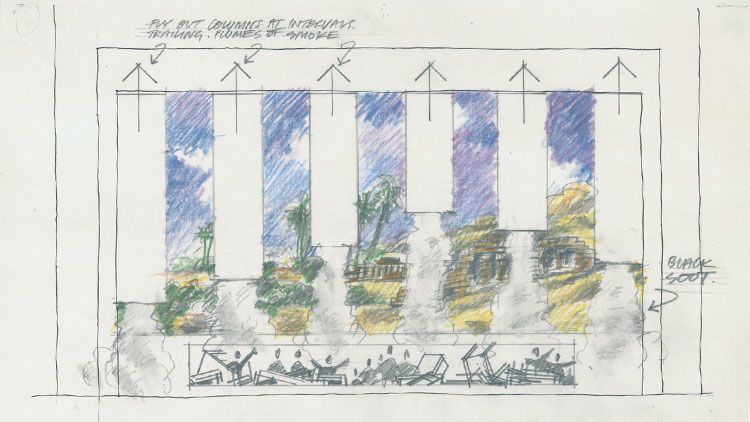

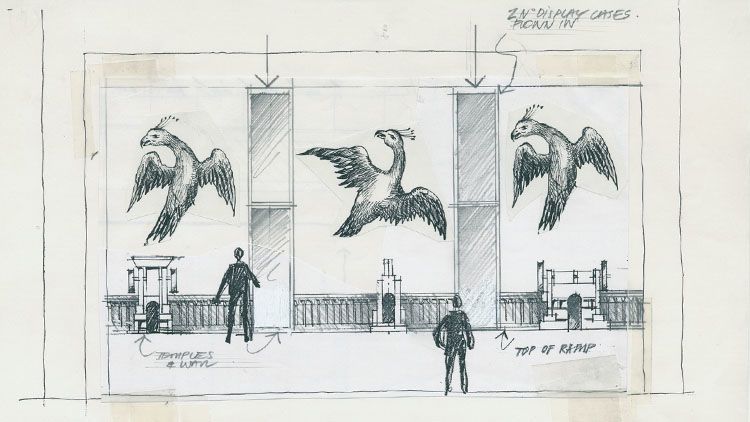

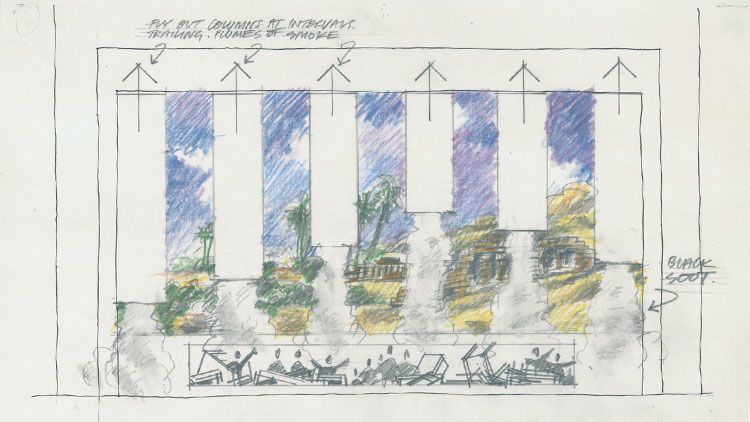

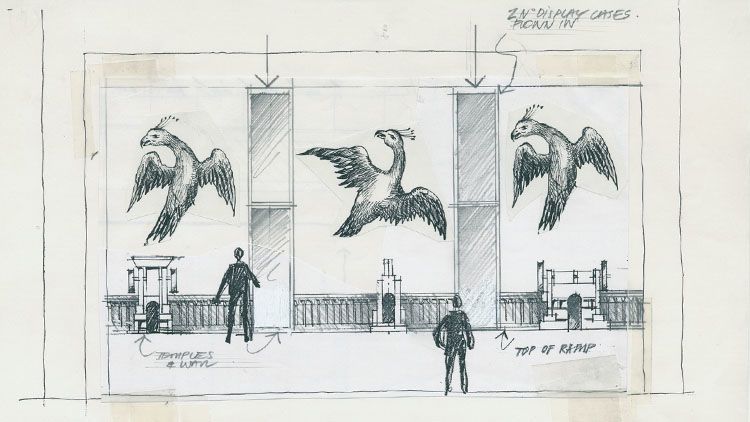

Early set design sketch by Peter Corrigan, 1994

Nabucco was Verdi’s first big success: he had also been 28 when Nabucco premiered at Milan’s La Scala opera house in 1842. The opera is based on the Biblical story of the persecution of the Jews under Nebuchadnezzar – but for Verdi, fidelity to the source mattered less than stirring music – most famously, the chorus ‘Va, Pensiero’ – and dramatic emotional expression.

Early set design sketch by Peter Corrigan, 1994

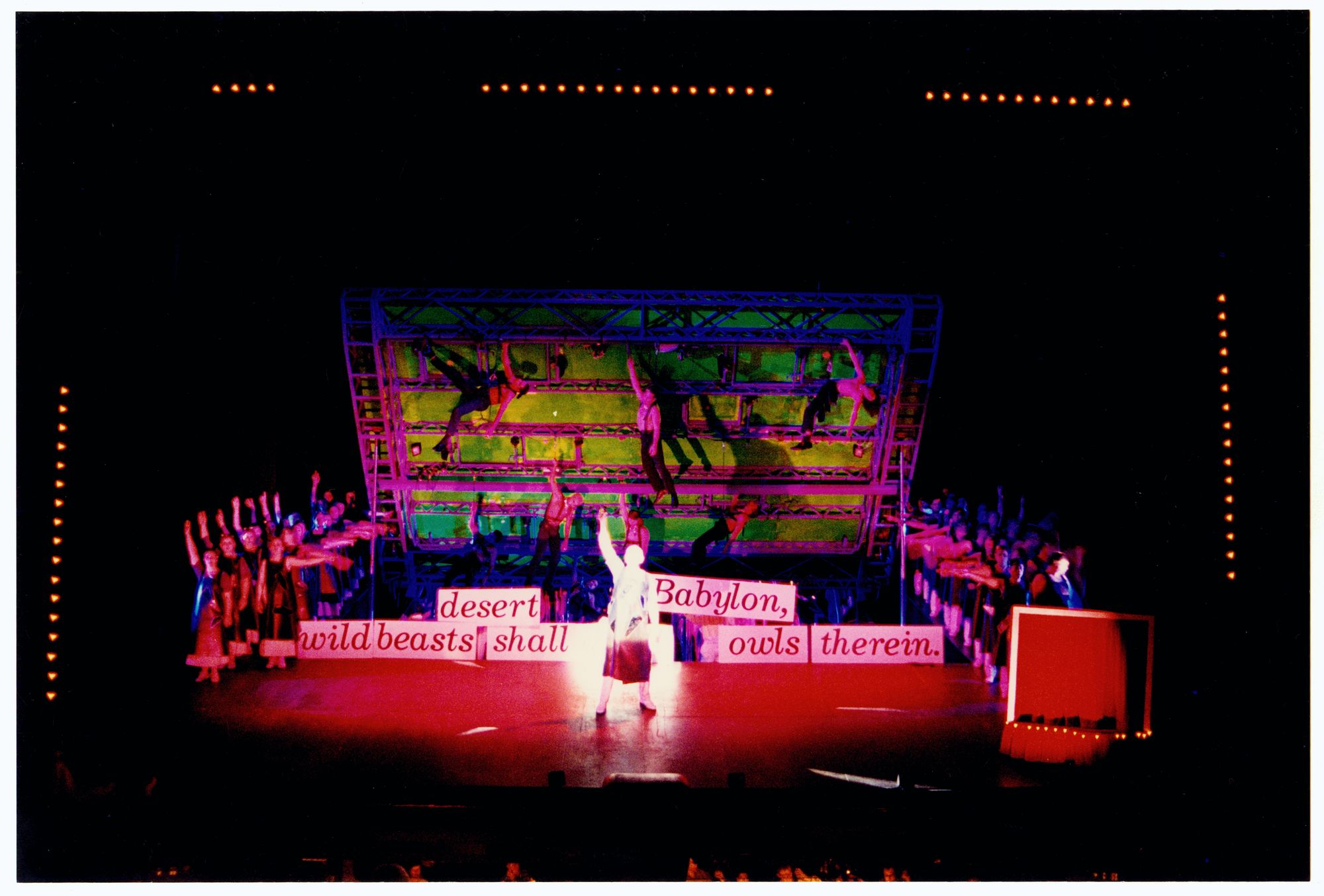

Kosky found the opera “a wonderfully weird archaeological puzzle… part-documentary, part-melodrama and part-historical variety show”. His approach was to start with the world of Italian opera where Nabucco had originated and, in his words, “explode [it] all over the stage”, imagining “a big 19th-century opera production on LSD” that moves from opera into vaudeville: “La Scala meets the Folies Bergeres goes to a Las Vegas casino”.

Elizabeth Connell and Jonathan Summers, inside a miniature theatre-within-a-theatre, 1996. Photograph by Jeff Busby.

Elizabeth Connell and Jonathan Summers, inside a miniature theatre-within-a-theatre, 1996. Photograph by Jeff Busby.

Corrigan’s design responded to Kosky’s vision of a “deliberately brash and somewhat hallucinogenic depiction of Babylon”. His costumes, sets and props were inspired by 19th-century opera productions, but also by images as diverse as wild animals, propaganda, and military uniform.

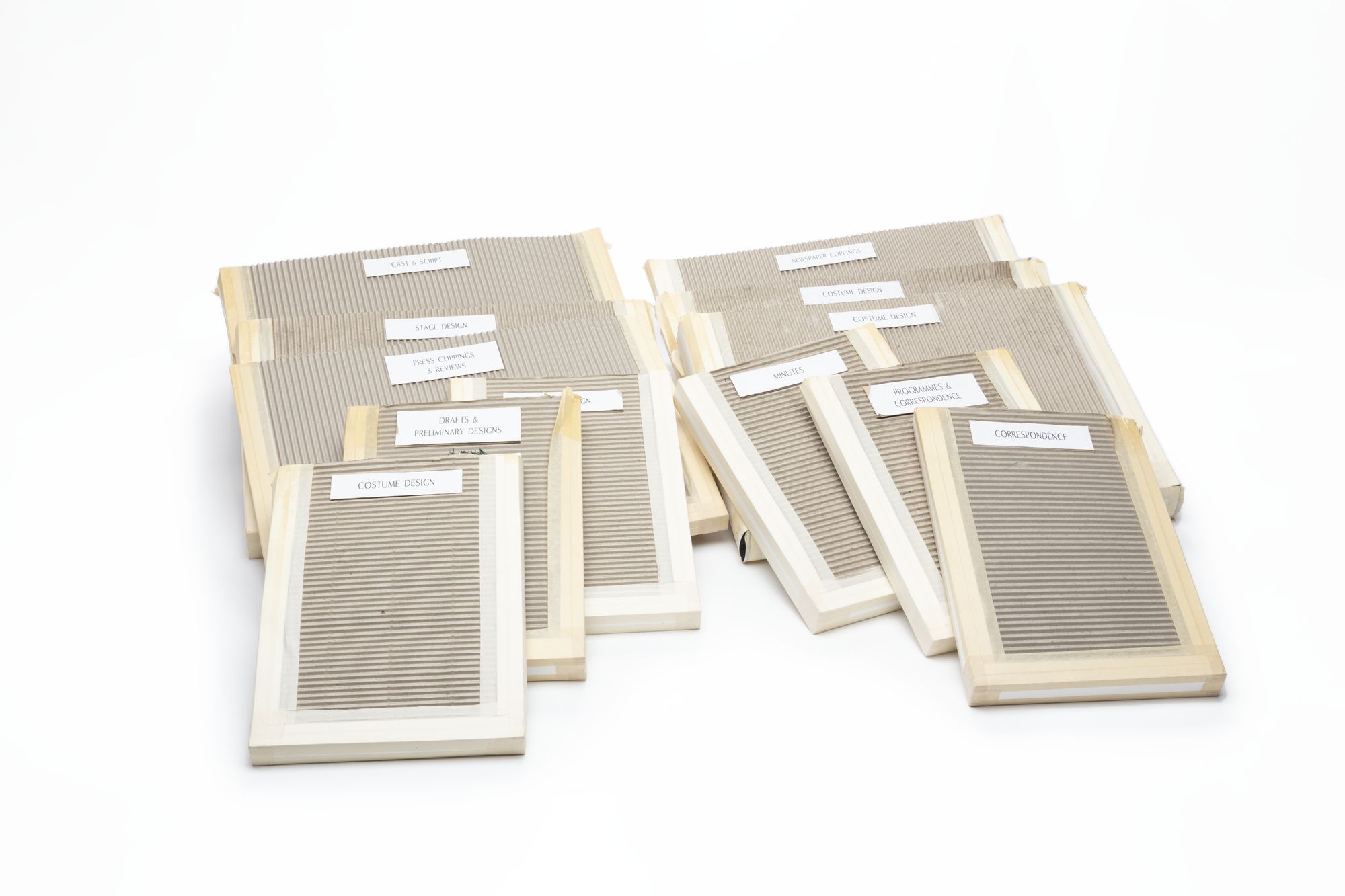

Peter Corrigan's design files for Nabucco

Peter Corrigan's design files for Nabucco

Peter Corrigan’s archive includes working sketches, notes and finished designs for Nabucco. Through them, we can see the evolution of his design ideas.

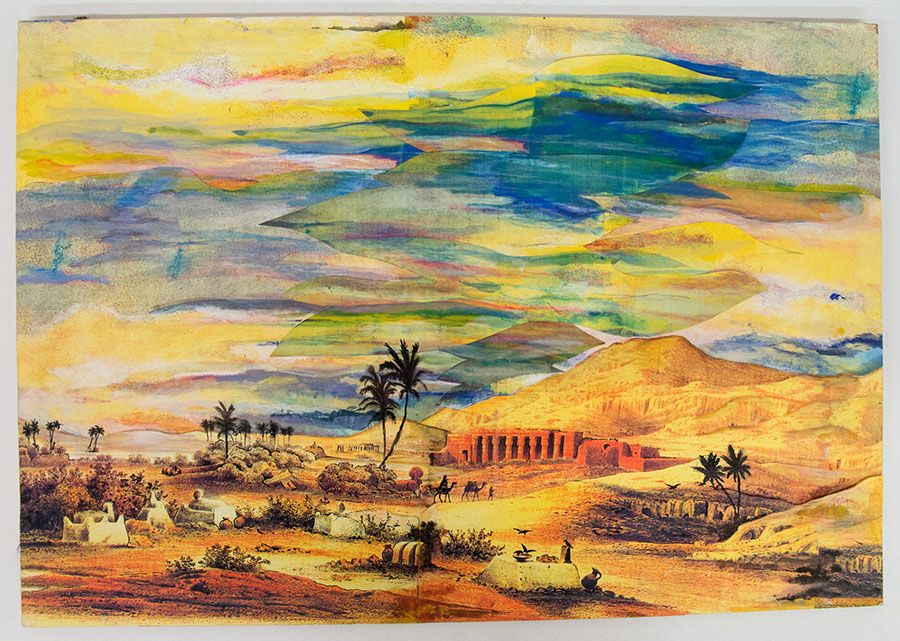

Early set design sketch by Peter Corrigan, 1994

Early set design sketch by Peter Corrigan, 1994

Early set design sketch by Peter Corrigan, 1994

Early set design sketch by Peter Corrigan, 1994

For the character of Nabucco, played by Malcolm Donnelly in Sydney and Jonathan Summers in Melbourne, Corrigan first sketched a suit like one worn by Paul Keating - but with a tiger skin over the shoulder.

The pencil sketch was photocopied and reworked.

The King's costume then evolved...

…into a full tiger-skin cloak

Colour and swatches made up the final design.

The result was a striking costume evoking Nabucco's regal power at the start of the opera.

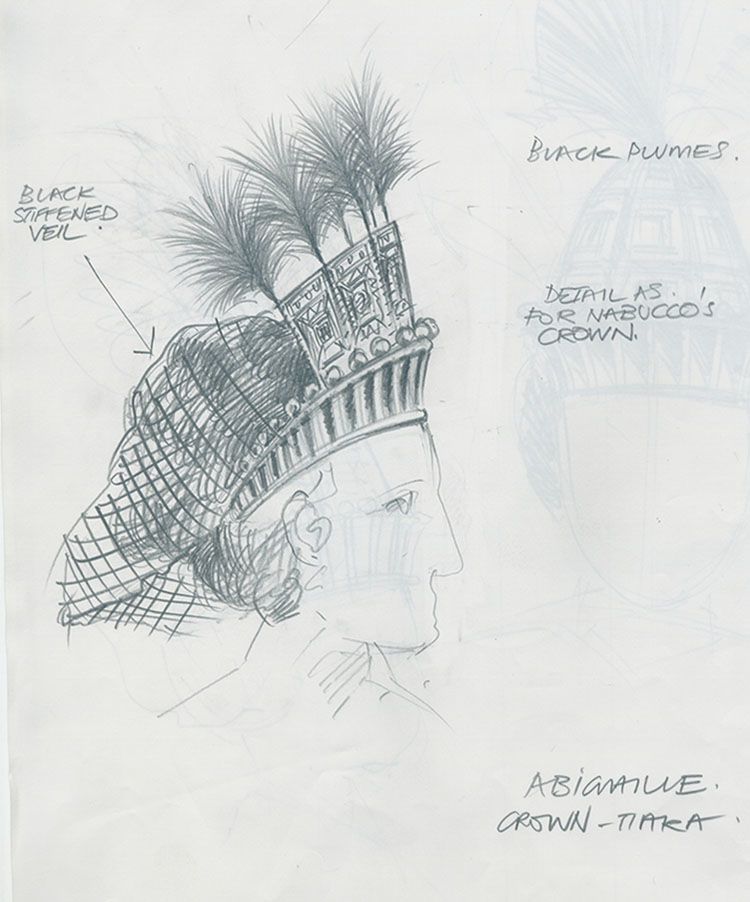

Corrigan also designed a series of costumes for the character Abigaille, played by Elizabeth Connell. These reflect her changing status – and state of mind – as she usurps power from Nabucco. In Act III, as Queen of Babylon, she wore a dress covered entirely in military medals, paired with a spectacular plumed tiara.

Costume worn by Elizabeth Connell as Abigaille, Act III, Nabucco, The Australian Opera, 1995-6

Costume worn by Elizabeth Connell as Abigaille, Act III, Nabucco, The Australian Opera, 1995-6

Realising the Vision

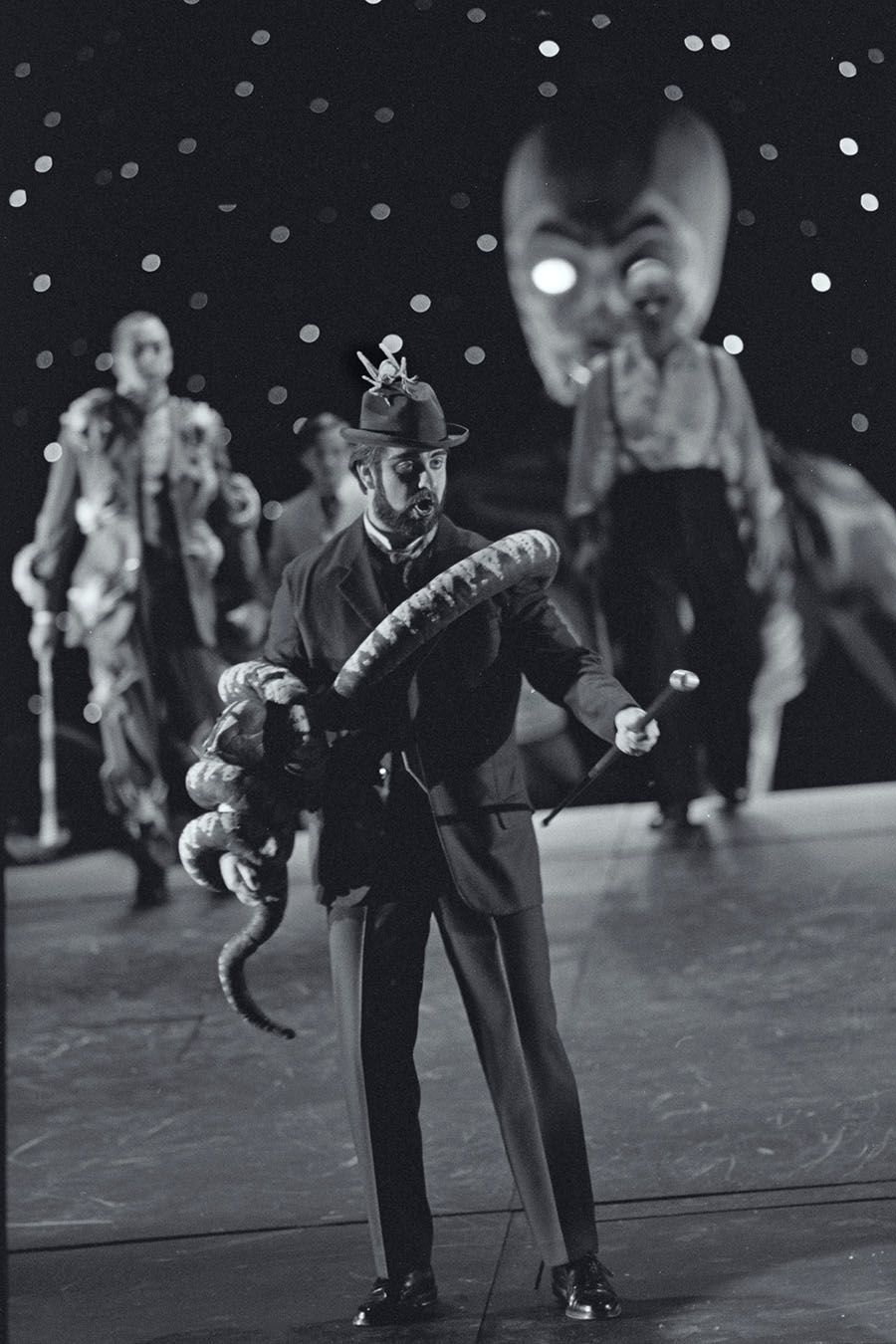

John Brunato as the High Priest Zaccaria

John Brunato as the High Priest Zaccaria

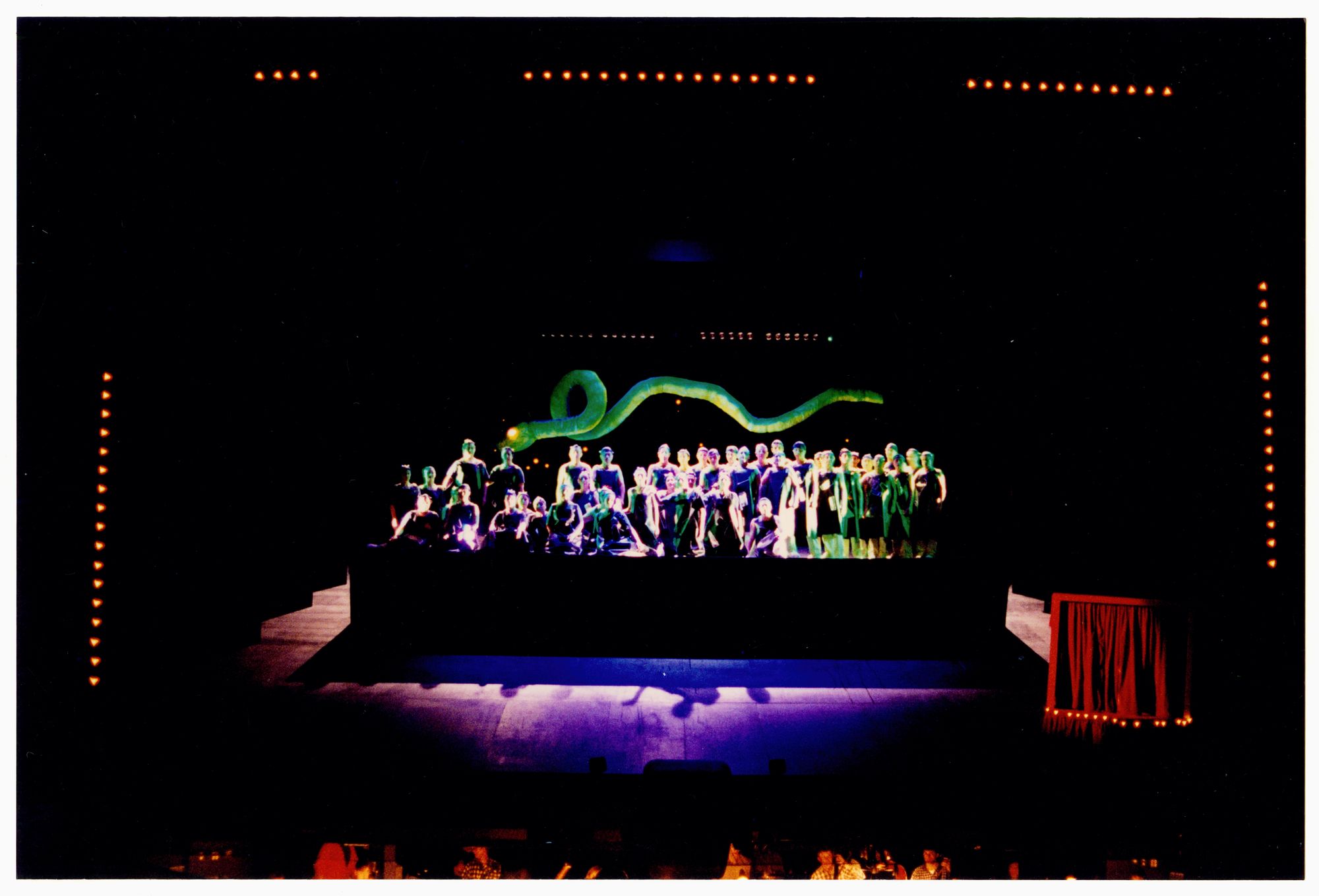

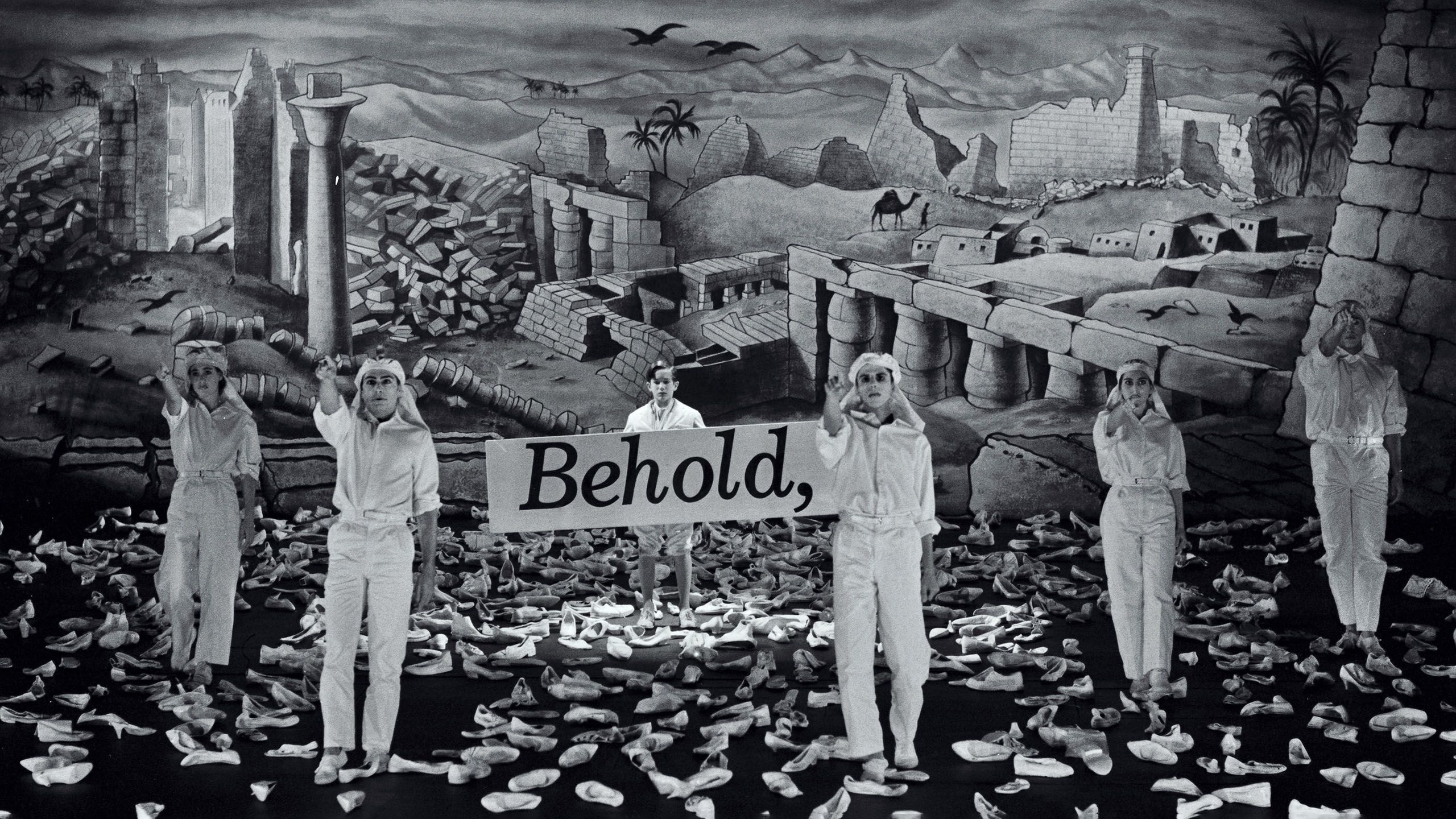

The chorus sing ‘Va Pensiero’

The chorus sing ‘Va Pensiero’

Realising Kosky and Corrigan’s vision for Nabucco was a challenge for The Australian Opera’s set builders, props and costume makers. The production was large in scale, with a budget of $350,000, and Kosky and Corrigan’s vision called for a giant serpent, enormous fibreglass heads, a stage that slid open, and of course the costumes for the eight principal singers and 50 chorus members.

Eliza Goldman, the head of Wardrobe, had to find ways of making the tigers' heads on the costumes light enough to wear while singing and moving on stage.

Scenery design by Peter Corrigan, 1995

Scenery design by Peter Corrigan, 1995

Corrigan also designed painted backdrops based on vintage prints. These evoked the scenery used in nineteenth century opera, but when combined with the contrasting modern stage elements, they deliberately undermined the Orientalist fantasy of an ‘exotic’ Middle East that such scenery implied.

Opening Nights

“Far better to boo, or to walk out, or bravo than to sit there and politely clap, and say, ‘Where are you going for supper?’”

When a section of the Sydney first-night audience booed the production, Barrie Kosky “looked like a boxer being congratulated at the end of an arduous match… He thought it was a fabulous reception; he loved the fact that the audience wasn’t bored – that they were either really excited by what they've seen”, said The Australian Opera’s communications director. Corrigan, too, was reported to have “smiled amiably”. Kosky later hinted at more complex feelings when he recalled “the glitter of tiaras and boozy faces of social first-nighters, faces made even more beetroot by my daring to depart from tradition”.

Headdress design by Peter Corrigan, 1994-5

Critical reception in Sydney was mixed. The Sun-Herald’s John Carmody wrote that “the complex originality and cheeky vitality of Barrie Kosky’s new production… provoked, amused and mystified me; it has had me pondering ever since.” Deborah Jones, in The Australian, was less amused, calling it an “incoherent, tarted up production… narrative counts for little here. The look is all, as the Babylonians sport animals’ heads on their costumes”. She called it “opera for the MTV set – flashy, cold, heartless, over-designed and deaf to the voice of the composer”.

Headdress design by Peter Corrigan, 1994-5

Meanwhile, letters of complaint poured in: one woman wrote that she had been “plunged into an abyss of horror”. Another wrote to newspapers to decry The Australian Opera’s “extravagant homo-erotic fantasies”. A further audience member wrote to complain that:

The original score set the opera in biblical times, but The Australian Opera took the liberty of allowing the 28-year-old Mr Kosky a free hand to set the opera in a surrealistic 21st century... I have taken the matter up with the general manager of The Australian Opera but he is of the opinion that to continue to produce operas in the traditional form is to keep the opera in a museum. If this is what The Australian Opera desires, it is free to do so, but it should inform prospective patrons that an opera is out of the ordinary. Accordingly, I am lodging a complaint with the Trade Practices Commission.

True to his word, the letter writer went to the Consumer Claims Tribunal, which ordered The Australian Opera to refund his $140 ticket costs.

Headdress design by Peter Corrigan, 1994-5

Headdress design by Peter Corrigan, 1994-5

Headdress design by Peter Corrigan, 1994-5

Headdress design by Peter Corrigan, 1994-5

Headdress worn by Elizabeth Connell as Abigaille, Act III, Nabucco, The Australian Opera, 1995-6

Headdress worn by Elizabeth Connell as Abigaille, Act III, Nabucco, The Australian Opera, 1995-6

“Many opera-goers expect to see a beautiful spectacle, not people waving placards and sneakers strewn all over the stage”

When Nabucco came to Melbourne in April 1996, the production’s controversial reputation preceded it.

But the reaction on opening night there was very different. Critic Bob Crimeen of the Sunday Sun-Herald recorded “a different kind of frenzy”:

“the opening night audience roaring unequivocal approval, and people stampeding to buy tickets to see one of the most excitingly staged, gloriously sung operas the national company has staged”

The Australian’s critic agreed that “There was a real sense that everyone, for whatever reason, was with Kosky, however crazy the staging was. At the end there were no boos, just tremendous cheers.”

Even though Crimeen felt Kosky had “inflicted some terrible atrocities” on Verdi’s work, he felt that “almost every moment offers new visual or dramatic wonders:

"It is impossible in one sitting to consume the bewildering banquet of theatrical… goodies served up by Kosky and designer Peter Corrigan, aided in no small measure by Nigel Levings’ superlative lighting design”

Perhaps Melburnians revelled in the chance to prove themselves more open-minded than Sydneysiders, or perhaps, The Age speculated, “this city is rather proud of our Barrie, who has done very well in a spectacularly short time”.

Headdress worn by Elizabeth Connell as Abigaille, Act I, Nabucco, The Australian Opera, 1995-6

Headdress worn by Elizabeth Connell as Abigaille, Act I, Nabucco, The Australian Opera, 1995-6

The Legacy

Since 1995, Barry Kosky has become internationally renowned as a director of theatre and opera, working in Austria, Germany, the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. He continues to radically reinterpret well-known works, finding new perspectives on much-performed classics.

Hat worn by John Brunato as the High Priest Zaccaria, Nabucco, The Australian Opera, 1995-6

Through his career, Kosky has developed the approach to opera that he laid out in a passionately-argued defence of Nabucco in the Sydney Morning Herald in 1995. In it, he argued that “Yes, the production is part-fantasy, part-burlesque, part-history lesson and part-spectacle, but so is the opera... Nabucco is about destruction, colonial power, metropolitan vulgarity, nostalgia, madness and history”. For Kosky, opera itself was "extravagant, confusing, entertaining, alarming and ecstatic". So for opera to continue to develop as a living artform, it needed to embrace this nature.

John Brunato as the High Priest Zaccaria. Photograph by Jeff Busby, 1996.

John Brunato as the High Priest Zaccaria. Photograph by Jeff Busby, 1996.

The designs and costumes in the Australian Performing Arts Collection show the full scope of Kosky and Corrigan's vision and the breadth of imagination they brought to the work. They remind us that the evolution of a living artform will not always be welcomed at first, but the passage of time can bring new appreciation, even if not always comprehension.

As Kosky told the Sunday Age as Nabucco opened in Melbourne, opera is “inexplicable in its power and mystery, so I think it should be more inexplicable and strange and more alluring. That’s why people go.”

Hat worn by John Brunato as the High Priest Zaccaria, Nabucco, The Australian Opera, 1995-6

Hat worn by John Brunato as the High Priest Zaccaria, Nabucco, The Australian Opera, 1995-6

Credits

Production costume and set designs by Peter Corrigan. Gift of Peter Corrigan, 2014, and Bequest of Peter Corrigan, 2019

Black and white production photographs from Melbourne season courtesy of Jeff Busby

Colour production photographs from the Peter Corrigan collection, photographer unknown. Gift of Peter Corrigan, 2014, and Bequest of Peter Corrigan, 2019

Costume photography by Narelle Wilson

With thanks to Larry Edwards for his investigation of Jonathan Summers' costume for the title role of Nabucco

Hat worn by John Brunato as Zaccaria the High Priest in Nabucco, The Australian Opera, 1995-6

Designed by Peter Corrigan and realised by The Australian Opera workshop

Gift of Opera Australia, 2013

Barry Kosky, c. 1995. Photographer unknown. Australian Performing Arts Collection, Arts Centre Melbourne.

Barry Kosky, c. 1995. Photographer unknown. Australian Performing Arts Collection, Arts Centre Melbourne.

Peter Corrigan, c. 2000. Photographer unknown. Photograph courtesy of Matthew Corrigan.

Peter Corrigan, c. 2000. Photographer unknown. Photograph courtesy of Matthew Corrigan.

Costume worn by Jonathan Summers as the title character in Nabucco, The Australian Opera, 1996

Designed by Peter Corrigan and realised by The Australian Opera workshop

Gift of Opera Australia, 2013

Costume worn by Elizabeth Connell as Abigaille in Nabucco, The Australian Opera, 1995-6

Designed by Peter Corrigan and realised by The Australian Opera workshop

Gift of Opera Australia, 2013