Worlds of Imagination

Miniature marvels from 40 years of the Theatres Building

The Australian Performing Arts Collection at Arts Centre Melbourne includes set models from landmark Australian productions, including those staged in Arts Centre Melbourne’s Theatres Building, which celebrates its 40th anniversary in 2024. Since opening in 1984, the three stages under the Spire – the Fairfax Studio, the Playhouse, and the State Theatre – have hosted moments of great creativity, imagination and drama.

By reproducing the design of sets and props in miniature, set models show how different designers created their own worlds on stage, and provide a lasting record of some of these key moments in Australian performing arts. The performances may be over, but through these models, their memory lives on.

The Theatres Building under construction. Photograph by Rick Altman

The opening night of the Theatres Building, 1984

Set model by Kenneth Rowell for The Sentimental Bloke, The Australian Ballet, 1984

Set model by Kenneth Rowell for The Sentimental Bloke, The Australian Ballet, 1984

George Bernard Shaw's Misalliance is set entirely in the conservatory of an English country house...

The model shows how Tony Tripp's set ingeniously creates a sense of light and space...

...with furniture carefully placed for the characters to converse...

...and a sense of decay amidst the grandeur.

Set models can be exquisitely crafted and beautiful objects. But they are made as working tools, a key part of the process of creating a show. A scale model helps designers test ideas in three dimensions, working out scenery, props and sightlines.

A model is also a collaborative tool. First, it can be used as a basis for discussion with the show’s director, lighting designer and production manager. Often the final model is preceded by a simpler white card model which quickly demonstrates the designer’s initial concept.

“Often the best ideas come 'on the go', including input from the other people involved in the production.”

The model also helps the creative team work out details of staging, lighting and costings. Then it becomes a reference for the prop-makers, set-builders, scenic artists and other production staff who will realise the creative vision.

Meanwhile, the cast are shown the model at the start of rehearsals, and often it will stay in the rehearsal room, helping them shape their roles with knowledge of the space they will inhabit on stage.

“One thing they always have to provide for the directors and the dancers and the actors, is a sense of the space that they are going to be working in… so the people involved can know what’s available to them.”

Hugh Colman was commissioned to design the ballet that would be performed in the State Theatre at the opening night of the Theatres Building: The Sleeping Beauty. It was the biggest stage he had designed for so far. A bigger stage meant a bigger model, as all set models are made to an exact scale: usually 1:25, where a human figure is about 7cm tall.

Although the new theatre had Australia’s biggest stage and exciting new possibilities, choreographer Maina Gielgud’s vision for The Sleeping Beauty was for a sumptuously traditional production of this historic work.

“Even though it was all brand new and exciting, the production that I did of The Sleeping Beauty was very traditional. We were very much approaching the work almost from a 19th century perspective. It was a very deliberate choice by the choreographer.”

The process of designing for the brand-new theatre was the same as had been passed down to Colman by the older generation of designers. Naturally, that meant a handmade model, the surviving parts of which Colman has recently donated to the Australian Performing Arts Collection.

Set model designed by Hugh Colman for Daylight Saving, Melbourne Theatre Company, 1990

Set model designed by Hugh Colman for Daylight Saving, Melbourne Theatre Company, 1990

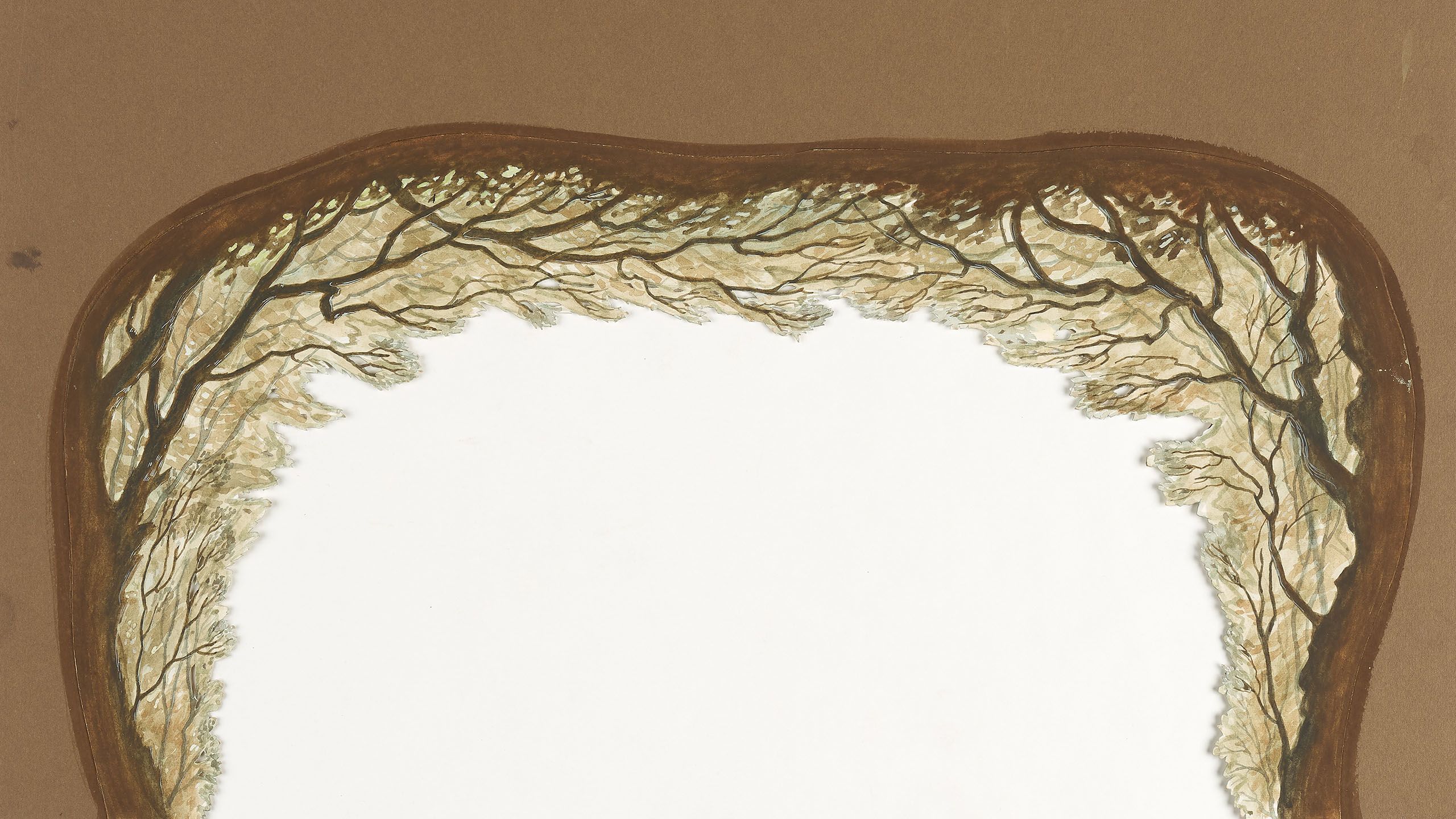

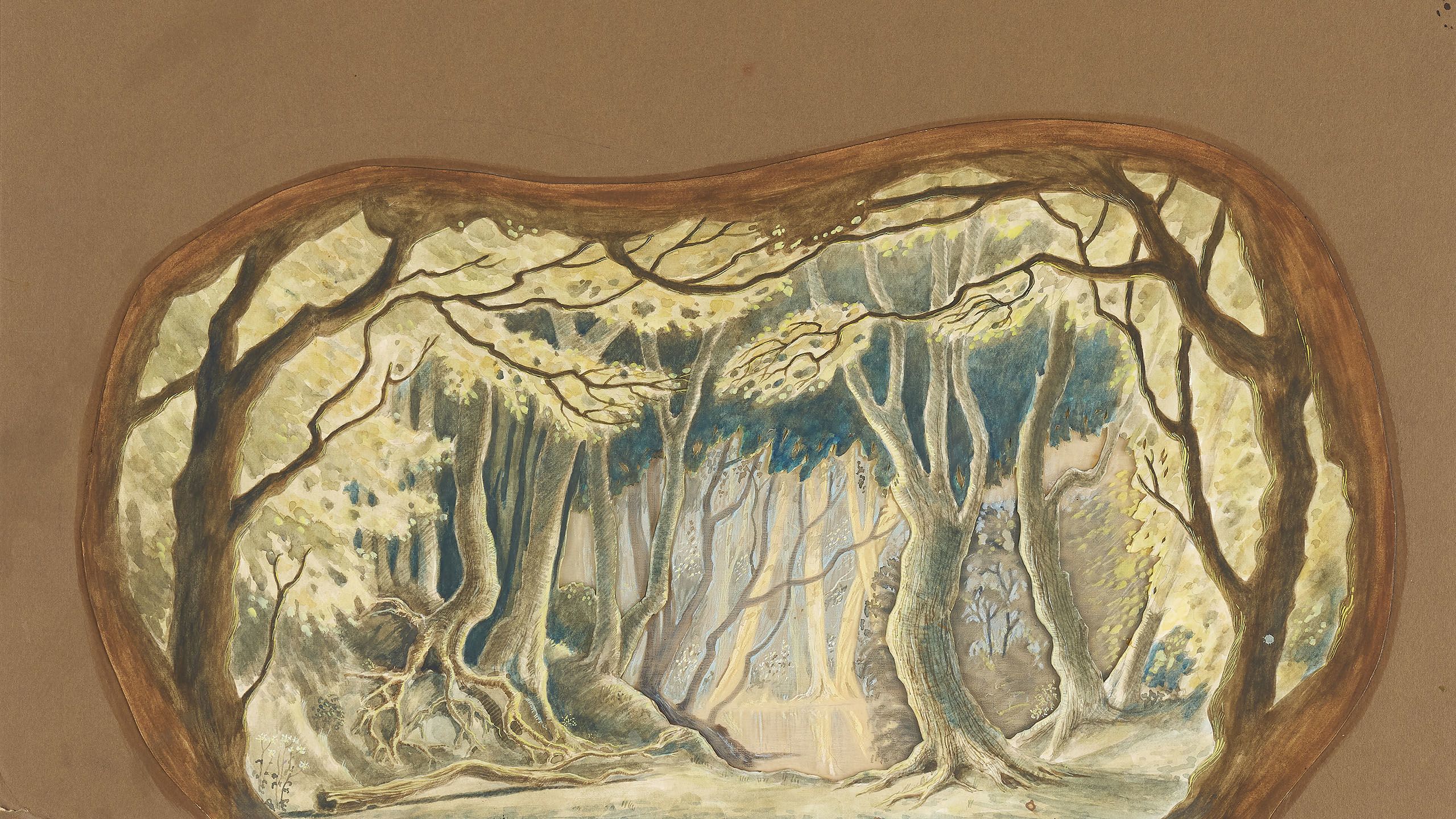

Scrim design, part of set model designed by Hugh Colman for Snugglepot and Cuddlepie, The Australian Ballet, 1988

Scrim design, part of set model designed by Hugh Colman for Snugglepot and Cuddlepie, The Australian Ballet, 1988

Set models are three dimensional...

...but they can work with the traditional scenic method...

...of multiple flat layers of scenery 'flown' from above...

...which themselves can use illusionistic effects to enhance the sense of depth.

Set models are traditionally presented in a box, scaled to the exact size of the intended venue’s stage and the proscenium arch above it.

But not all theatres have this traditional layout. For Arts Centre Melbourne's Theatres Building, it was intended from the start to include a flexible ‘black box’ space for experimental theatre and other performance: the Studio (now the Fairfax Studio).

Nigel Triffitt, one of the most innovative theatre-makers of the 1980s, was commissioned to devise a show for the Studio's opening season.

Triffitt devised, designed and directed spectacular visual theatre productions that combined music, puppetry, acting and movement.

Each of his shows featured extraordinary sculptural sets, and The Gift of Vagrancy was no exception, showing off the Studio's potential for theatre 'in the round' with sets for a series of scenes, each modelled before construction.

Indeed, when Triffitt was commissioned to develop a show, the first thing he would do was buy balsa wood. “I have a close relationship with a hobby shop on Lonsdale Street, where I go on a daily basis”, he told The Age in 1987.

One room of Triffitt’s two-room Melbourne apartment would then be devoted to model-making:

“As soon as I cut the first piece of balsa wood I am there until I finish it. I can’t get out. It can take overnight or months – that’s all I do”.

Triffitt saw a model as replacing the need for set drawings completely. He explained that “You see, the model and what appears on stage is exact. People think they understand a drawing, but they don’t. A model is a model and it’s in scale. It’s the quick and easy way to work. You give people the model, they build it.”

He also appreciated the appeal of models as objects:

“I look at them as being sculpture… I know the most ordinary people respond to the craft of them; it’s like dolls’ houses. If I present a design as a model rather than a drawing, they will accept it even if it’s no good. The main reason is that everybody can understand the three-dimensional nature of a model.”

Triffitt donated his collection of set models to the Collection in 1998, and they form a striking record of his extraordinary visual imagination.

Nigel Triffitt's model for The Gift of Vagrancy, 1984

Nigel Triffitt's model for The Gift of Vagrancy, 1984

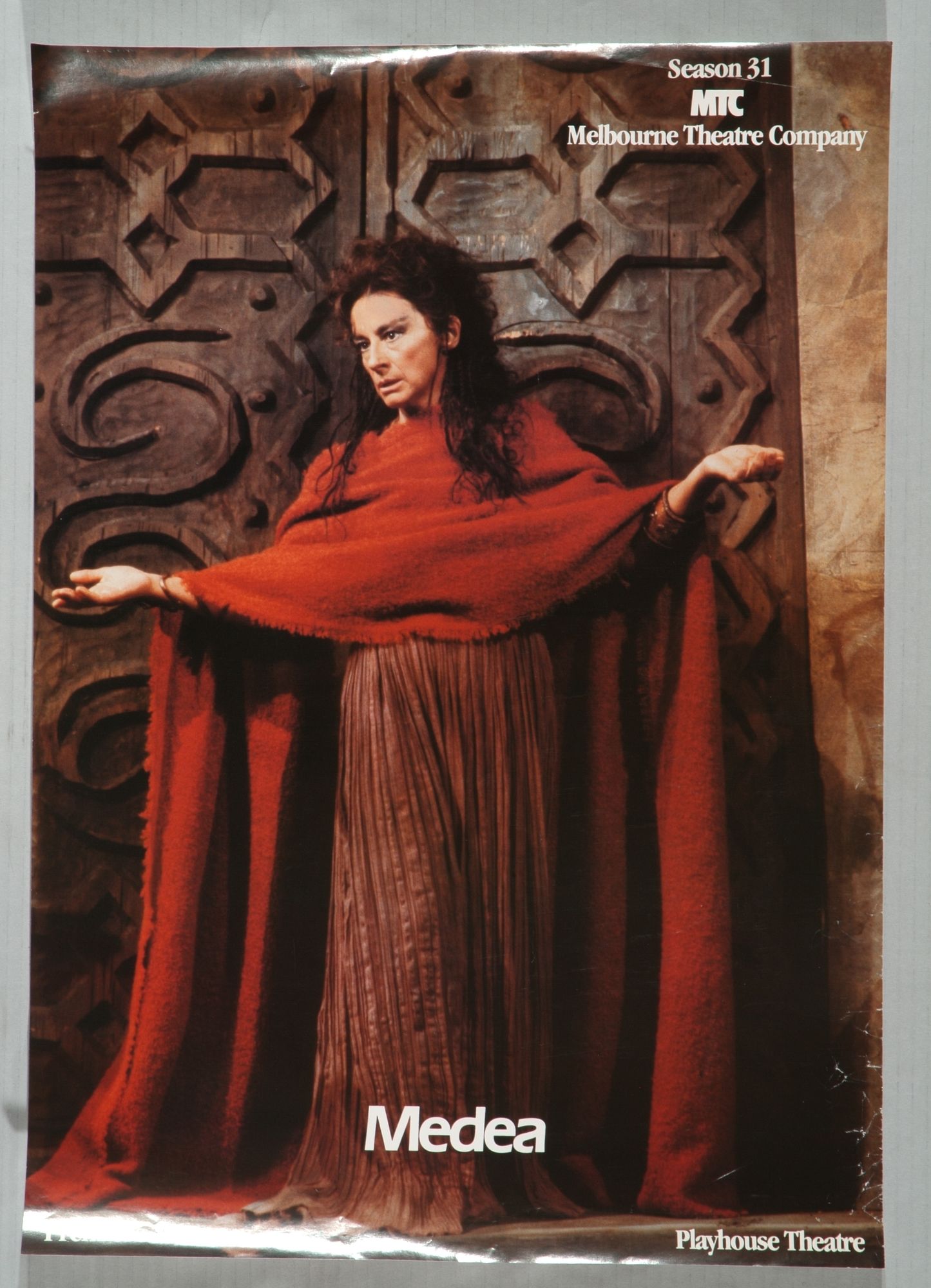

When Arts Centre Melbourne’s Playhouse opened 40 years ago, the first performance was a dramatic return to Melbourne by Zoe Caldwell.

It was a historic moment – the opening of a new theatre, Caldwell’s first performance in Australia since 1962, and her return to Melbourne Theatre Company, with whom she had performed in their very first season (as the Union Theatre Repertory Company) in 1953.

The set for Caldwell’s performance contributed to its dramatic force – a stark Greek temple in a bleak stone landscape, whose doors opened at a climactic moment to reveal the bodies of her children.

We can look back at this play 50 years later and understand how it could have worked on stage by looking at the set model that was made as part of the production process.

Kenneth Rowell's set model for the Australian Ballet's The Sentimental Bloke (1985) shows the different settings of Bill and Doreen's courtship, from a Melbourne pickle factory...

...to St Kilda beach...

...and the Melbourne Cup.

The Australian Performing Arts Collection has been collecting set models from its earliest days. In 1978, as a gift to the new collection, playwright Ray Lawler, on behalf of Melbourne Theatre Company, handed over a model by Anne Fraser of the previous year’s production of his Summer of the Seventeenth Doll.

Model designed by Anne Fraser for Summer of the Seventeenth Doll, 1977. Gift of the Melbourne Theatre Company, 1978

Model designed by Anne Fraser for Summer of the Seventeenth Doll, 1977. Gift of the Melbourne Theatre Company, 1978

Later the company donated the set model from their 1995 anniversary production of the same play, designed by Tony Tripp.

Tripp's design takes us into the Carlton terrace house where the characters of the play meet for another summer.

Within the 1950s interior, scenery and props are meticulously modelled...

...down to the bowl of fruit on the table...

...and of course the Kewpie dolls from the previous sixteen years.

In 2008 MTC donated their model for a production of The Importance of Being Earnest, directed by Simon Phillips and designed by Tony Tripp, that was performed in the Playhouse in 1988. Tripp created an ingenious revolving set, placing the characters as if in a book illustrated by Oscar Wilde’s contemporary Aubrey Beardsley.

In 2011, to mark the end of Phillips’ tenure as Artistic Director, MTC restaged the production. Production staff visited the collection to view the model, as they recreated the original sets. The set model conveys the feel of each scene more vividly than any two-dimensional drawing.

Set model designed by Tony Tripp for The Importance of Being Earnest, Melbourne Theatre Company, 1988

Set model designed by Tony Tripp for The Importance of Being Earnest, Melbourne Theatre Company, 1988

"There are so many things that you don't have to say that the model can say for you.

They are powerful. They really are at the heart of the process."

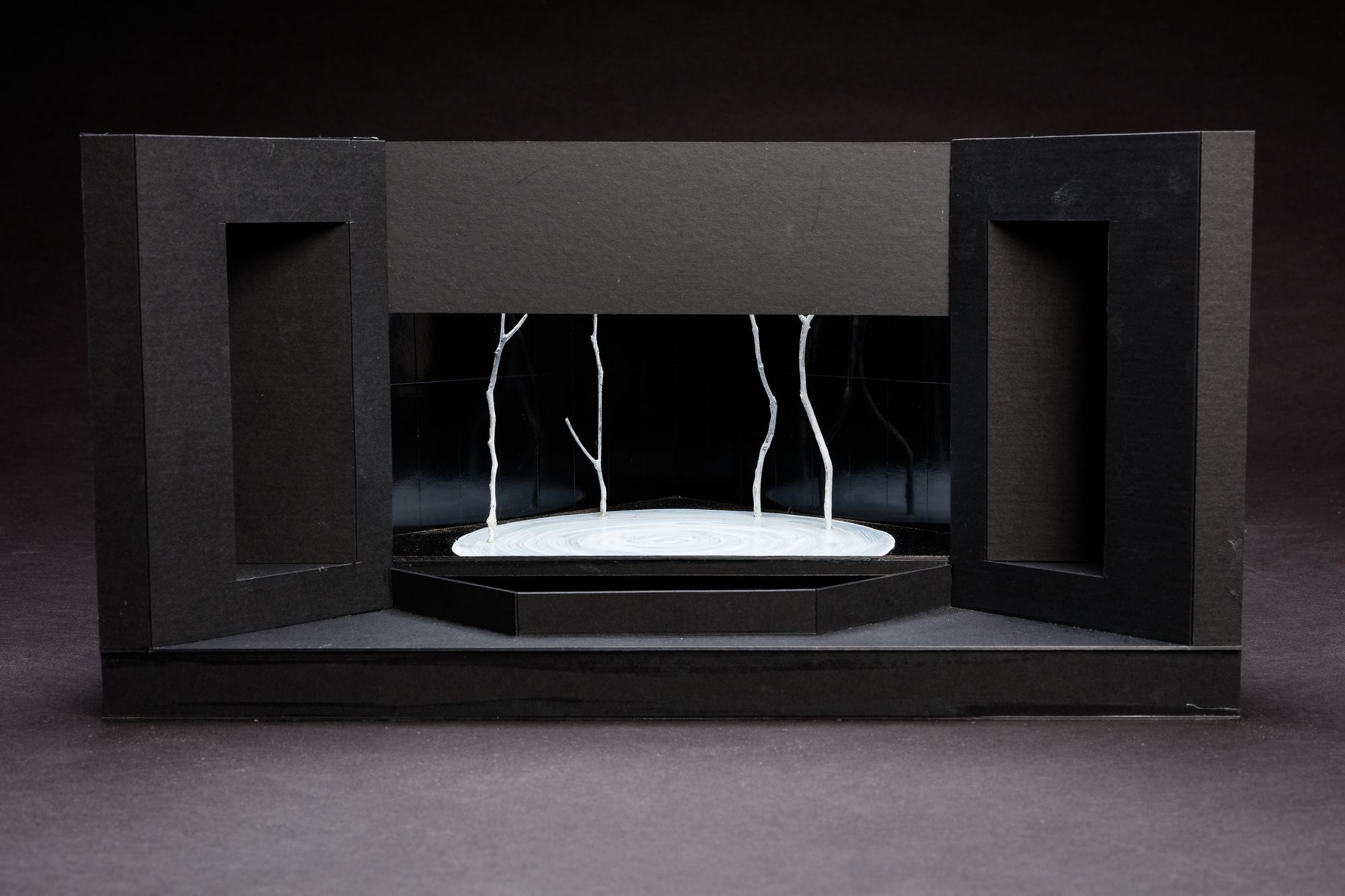

Richard Roberts, Head of Design at the Victorian College of the Arts (VCA), has designed many productions for the Theatres Building's stages, most recently his starkly atmospheric set for Victorian Opera's The Visitors.

For Roberts, design is about taking an idea that at first exists only in the designer's head, and giving it a form in the real world. He teaches his students to make a series of models as part of this process. These models become a vital communication tool: "When I'm trying to articulate to students why we make models, I describe to them the experience of the first day of rehearsals of a new show", he explains.

The model sits on a table in the rehearsal room under a cloth. "All the actors come in. You have been working on the design for months, but it is Day One for them. And you want to bring them up to speed. Now, you could make a speech. And it would take a really long time to describe all the things you're going to do. But the other way is to pull the black cloth off the model and just show them."

"It's interesting how much information can be conveyed by just looking at the model. Colour, texture, materiality, scale. How does it fit into the theatre? Where are the exits and entrances? What's the relationship between the audience and the actor? What's the style, what's the period?

For Roberts, digital design tools cannot compete with the tactile appeal of a model: "With craftspeople in particular, but also with actors and directors, they want to be able to hold it in their hand and turn it around themselves. You can't do that through a screen."

The qualities that make set models a powerful tool for communication before a show, also make them among the most meaningful remnants left after the final curtain falls. Roberts feels that set models from previous productions are "quite precious things", because once a performance is over, they can be almost all that remains of an ephemeral art form.

The Australian Performing Arts Collection will continue to work with designers and companies to collect set models that reflect the creativity and ingenuity of Australian designers. With the art of the model being passed on to a new generation, they will continue to play a leading role in creating new shows on Arts Centre Melbourne's stages.

Visit Arts Centre Melbourne to see a selection of models from 40 years of the Theatres Building, now on display in Smorgon Family Plaza.

Credits

All set models and images are from the Australian Performing Arts Collection, Arts Centre Melbourne, unless otherwise stated

Online story by Ian Jackson, Curator, Dance and Opera, Australian Performing Arts Collection

With thanks to Hugh Colman and Richard Roberts

Set model designed by Tony Tripp for Misalliance, Melbourne Theatre Company, The Playhouse, 1998

Gift of Melbourne Theatre Company, 2008

Set model designed by Kenneth Rowell for The Sentimental Bloke, The Australian Ballet, State Theatre, 1985

Acquired 1986

Set model designed by Hugh Colman for Daylight Saving, Melbourne Theatre Company, 1990

Donated through the Australian Government's Cultural Gifts Program by Hugh Colman, 2015

Set model piece designed by Hugh Colman for Snugglepot and Cuddlepie, The Australian Ballet, State Theatre, 1988

Gift of Hugh Colman, 2024

Set model pieces designed by Hugh Colman for The Sleeping Beauty, The Australian Ballet, State Theatre, 1984

Gift of Hugh Colman, 2024

Set model designed by Nigel Triffitt for The Gift of Vagrancy, Victorian Arts Centre Trust, The Studio, 1984

Gift of Nigel Triffitt, 1998

Set model designed by Ben Edwards for Medea, Melbourne Theatre Company, The Playhouse, 1984

Gift of Melbourne Theatre Company, 1994

Set model designed by Anne Fraser for Summer of the Seventeenth Doll, Melbourne Theatre Company, Russell Street Theatre, 1977

Gift of Melbourne Theatre Company, 1978

Set model designed by Tony Tripp for Summer of the Seventeenth Doll, Melbourne Theatre Company, The Playhouse, 1995

Gift of Melbourne Theatre Company, 1995

Set model designed by Tony Tripp for The Importance of Being Earnest, Melbourne Theatre Company, The Playhouse, 1988

Gift of Melbourne Theatre Company, 2008

Set model designed by Richard Roberts for The Visitors, Victorian Opera, The Playhouse, 2023

Kindly lent by Richard Roberts

Poster for Medea, Melbourne Theatre Company, The Playhouse, 1984

Gift of Francoise Piron, 1997